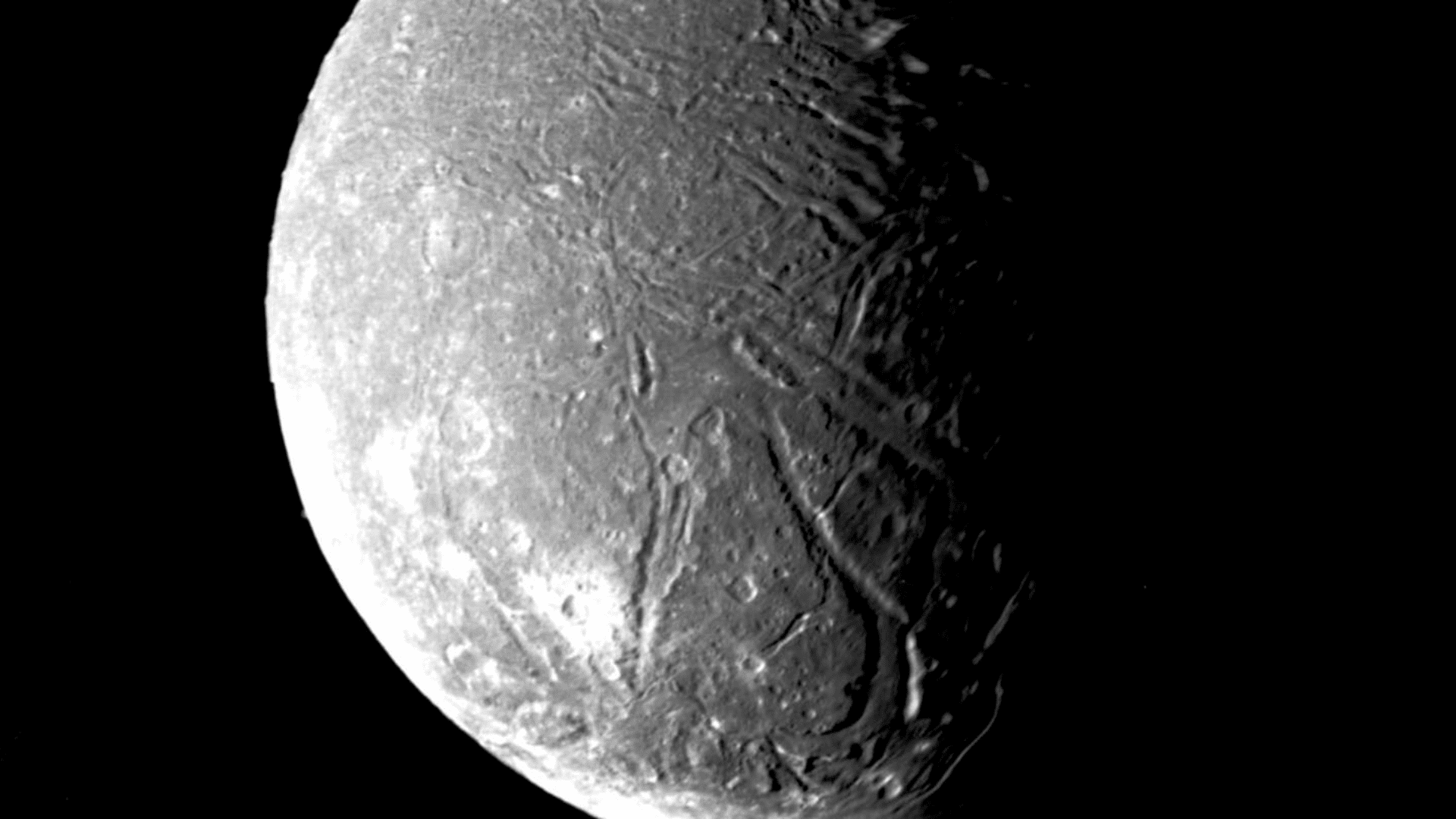

Researchers say Uranus’ moon Ariel is coated with significant carbon dioxide ice. This is especially apparent on its “trailing hemisphere,” which always faces away from the Sun. It’s surprising because even in its most frigid areas, carbon dioxide readily turns into gas. The coldest parts of the Uranian system are 20 times farther from the Sun than Earth.

A new theory suggests a possible liquid ocean under Ariel’s frozen surface.

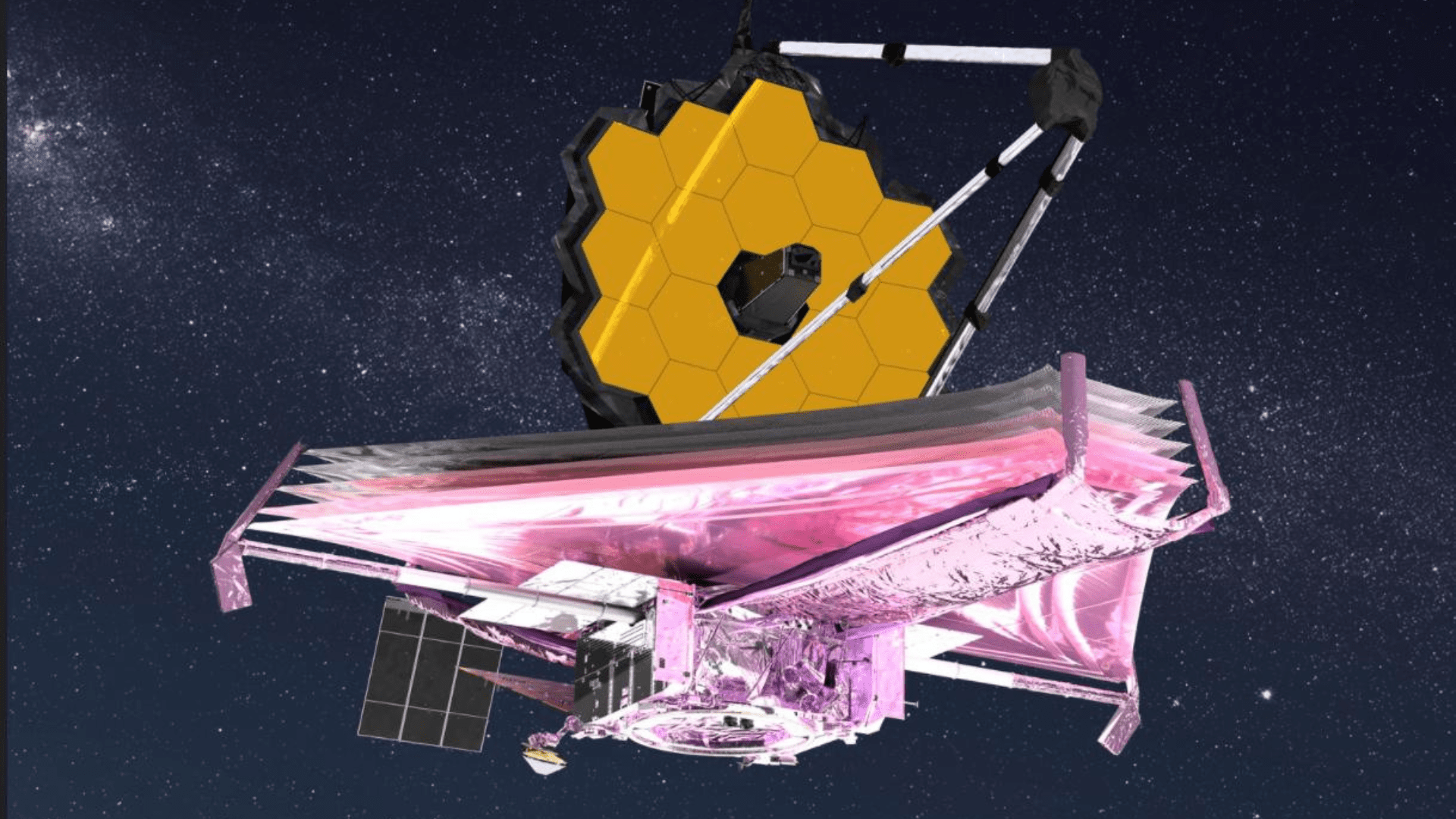

Using Webb Telescope

Scientists have theorized that something is supplying carbon particles to Ariel’s surface. However, some believe the carbon is created by a process called radiolysis, where molecules are broken down by ionizing radiation. A new study in The Astrophysical Journal Letters favors a different theory: carbon dioxide emerges inside the planet’s moon. Moreover, the carbon may come from a subsurface liquid ocean.

The James Webb Space Telescope collected chemical spectra from the moon. Then, a research team led by Richard Cartwright from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) compared them to simulated mixtures. Upon comparison, the researchers discovered that Ariel contains some of the most carbon-rich materials in the solar system. Among the results revealed another puzzling discovery: carbon monoxide.

“It just shouldn’t be there,” said Cartwright. “You’ve got to get down to 30 kelvins [minus 405 degrees Fahrenheit] before carbon monoxide’s stable.” Meanwhile, Ariel’s surface temperature averages 65 degrees F warmer. “The carbon monoxide would have to be actively replenished, no question.”

Producing CO and CO2

Cartwright believes radiolysis is responsible for replenishing some of the waste. However, lab experiments show that radiation strikes from water ice mixed with carbon-rich materials create carbon dioxide and monoxide. This explains radiolysis as a restocking source and accounts for the rich abundance of both CO and CO2 on Ariel’s trailing hemisphere.

There is a theory that a bulk of the carbon oxides come from a chemical process that once happened, or is currently happening, in an ocean under the icy surface. Researchers suggest the oxides slip through cracks or escape through eruptive plumes.

Additionally, observations hint at the possibility of Ariel’s surface containing carbonate minerals. Interestingly, carbonate minerals are salts created through the interaction of water with rocks.

“If our interpretation of that carbonate feature is correct, then that is a pretty big result because it means it had to form in the interior,” Cartwright said. “That’s something we absolutely need to confirm, either through future observations, modeling or some combination of techniques.”