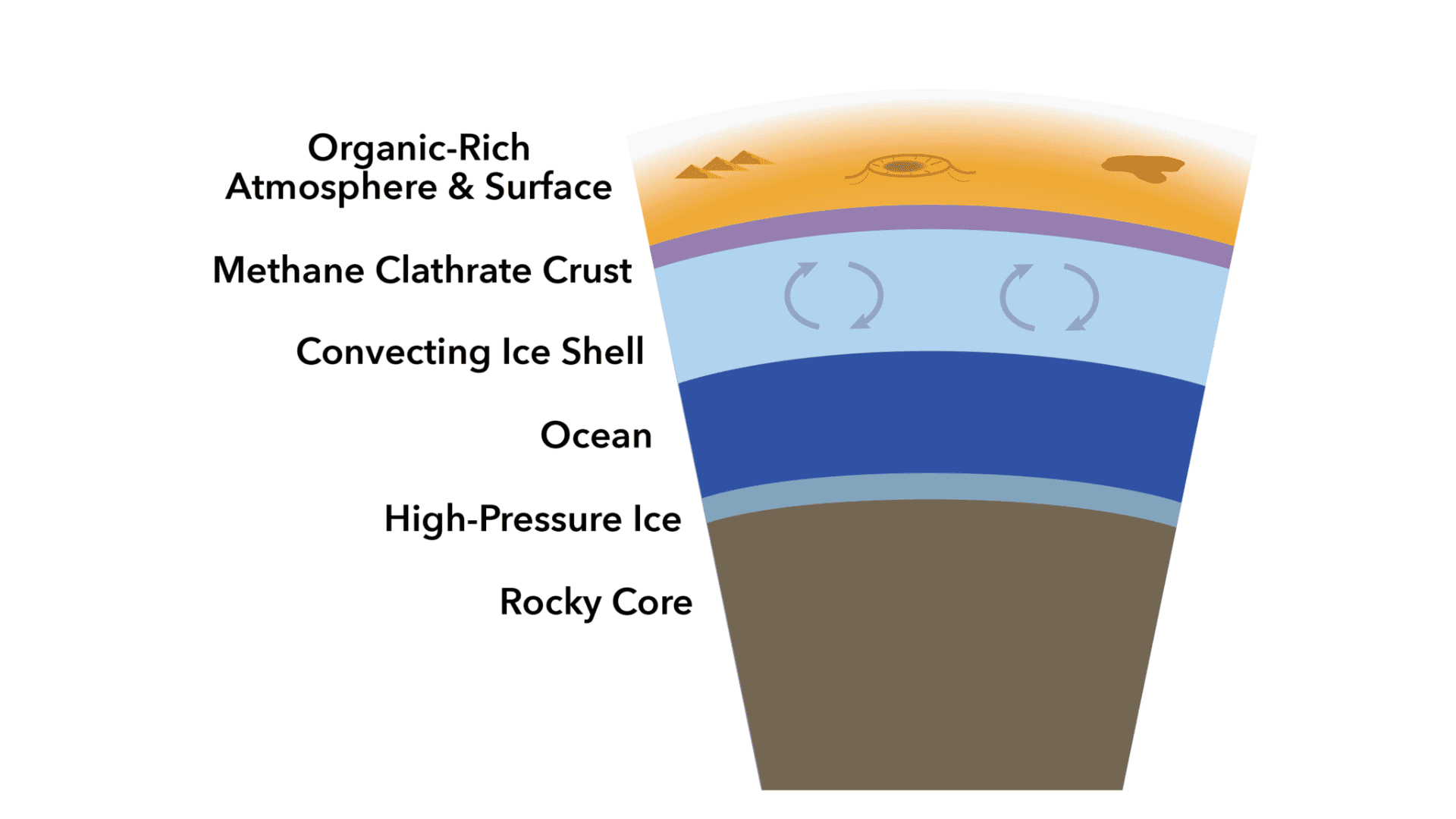

Titan is Saturn’s largest moon and the only place other than Earth with an atmosphere, rivers, lakes, and seas. Because of Titan’s extremely cold temperatures, its liquids are made of hydrocarbons like methane and ethane. The surface is also made of solid water ice.

Exploring Titan

Planetary scientists at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa led a new study revealing methane gas that might be trapped within the ice, “forming a distinct crust up to six miles thick.” They believe this warms the underlying ice shell and “may also explain Titan’s methane-rich atmosphere.”

After observing NASA data, the researchers discovered something interesting about the moon’s craters. They found that Titan’s impact craters are hundreds of meters shallower than expected, and only 90 have been identified.

“This was very surprising because, based on other moons, we expect to see many more impact craters on the surface and craters that are much deeper than what we observe on Titan,” said research associate Lauren Schurmeier, who also led the study. “We realized something unique to Titan must be making them become shallower and disappear relatively quickly.”

The researchers tested Titan’s topography in a computer model to investigate what’s behind this mystery. They specifically tested how the topography might relax or rebound “if the ice shell was covered with a layer of insulating methane clathrate ice,” a kind of solid water with methane gas trapped inside. Unfortunately, researchers don’t know the initial shape of Titan’s craters. However, they modeled and compared plausible initial depths based on fresh-looking craters of similar size on a similar moon, Ganymede.

“Using this modeling approach, we were able to constrain the methane clathrate crust thickness to five to ten kilometers [about three to six miles] because simulations using that thickness produced crater depths that best matched the observed craters,” said Schurmeier. “The methane clathrate crust warms Titan’s interior and causes surprisingly rapid topographic relaxation, which results in crater shallowing at a rate that is close to that of fast-moving warm glaciers on Earth.”

Titan’s Methane-Rich Atmosphere

Estimating the thickness of the methane ice shell is important because it may explain the origin of the methane-rich atmosphere. Additionally, it helps researchers understand the carbon cycle, liquid methane-based “hydrological cycle,” and changing climate.

“Titan is a natural laboratory to study how the greenhouse gas methane warms and cycles through the atmosphere,” said Schurmeier. “Earth’s methane clathrate hydrates, found in the permafrost of Siberia and below the arctic seafloor, are currently destabilizing and releasing methane. So, lessons from Titan can provide important insights into processes happening on Earth.”

The new findings help explain the moon’s topography. According to the researchers, “Titan’s interior is likely warm–not cold, rigid, and inactive as previously thought.”

“Methane clathrate is stronger and more insulating than regular water ice,” said Schurmeier. “A clathrate crust insulates Titan’s interior, makes the water ice shell very warm and ductile, and implies that Titan’s ice shell is or was slowly connecting.”

“If life exists in Titan’s ocean under the thick ice shell, any signs of life (biomarkers) would need to be transported up Titan’s ice shell to where we could more easily access or view them with future missions,” Schurmeier added. “This is more likely to occur if Titan’s ice shell is warm and connecting.”

The NASA Dragonfly mission to Saturn’s icy moon will launch in July 2028 and arrive in 2034. This mission will allow researchers to observe the moon closely and investigate its icy surface.