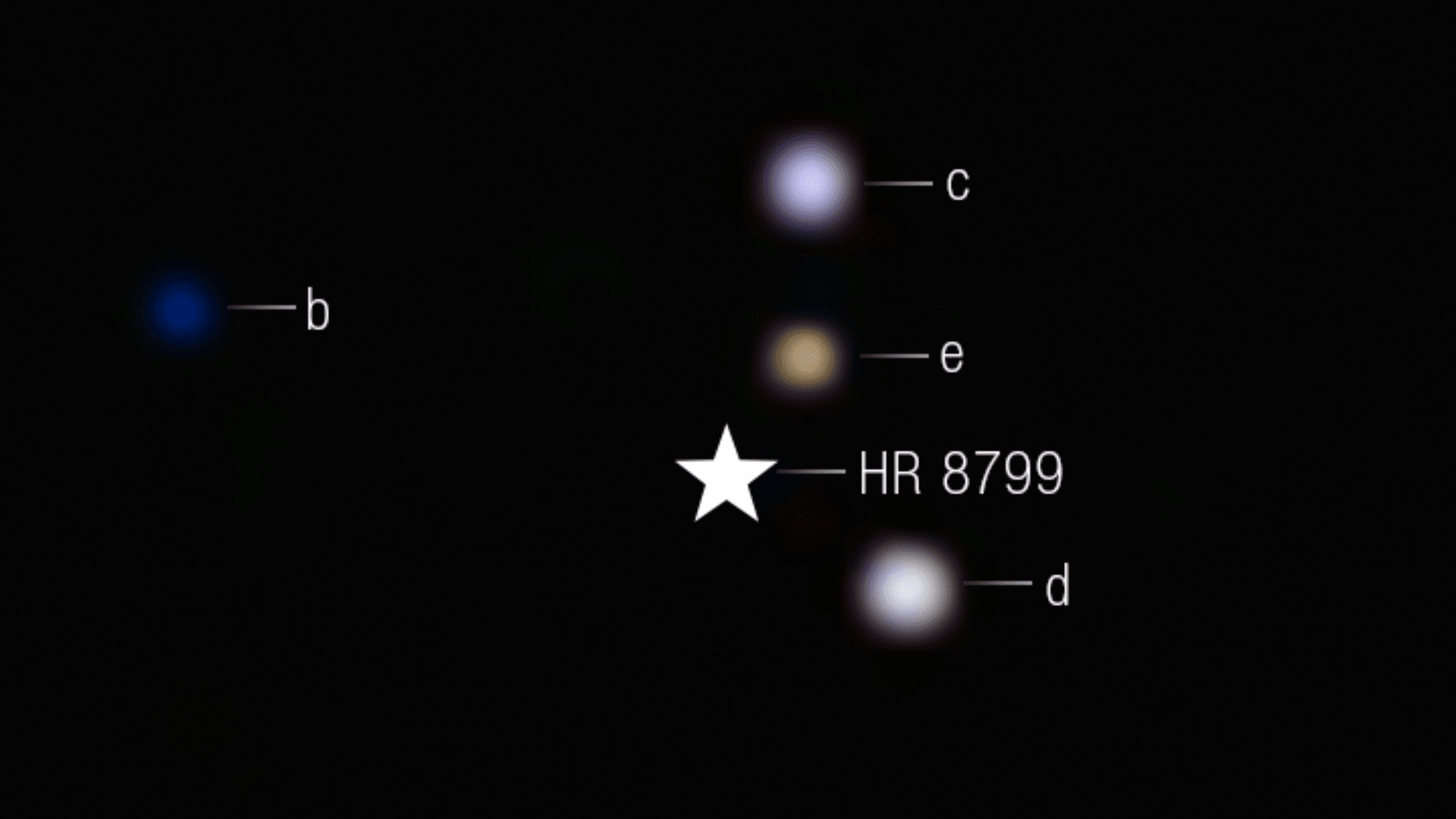

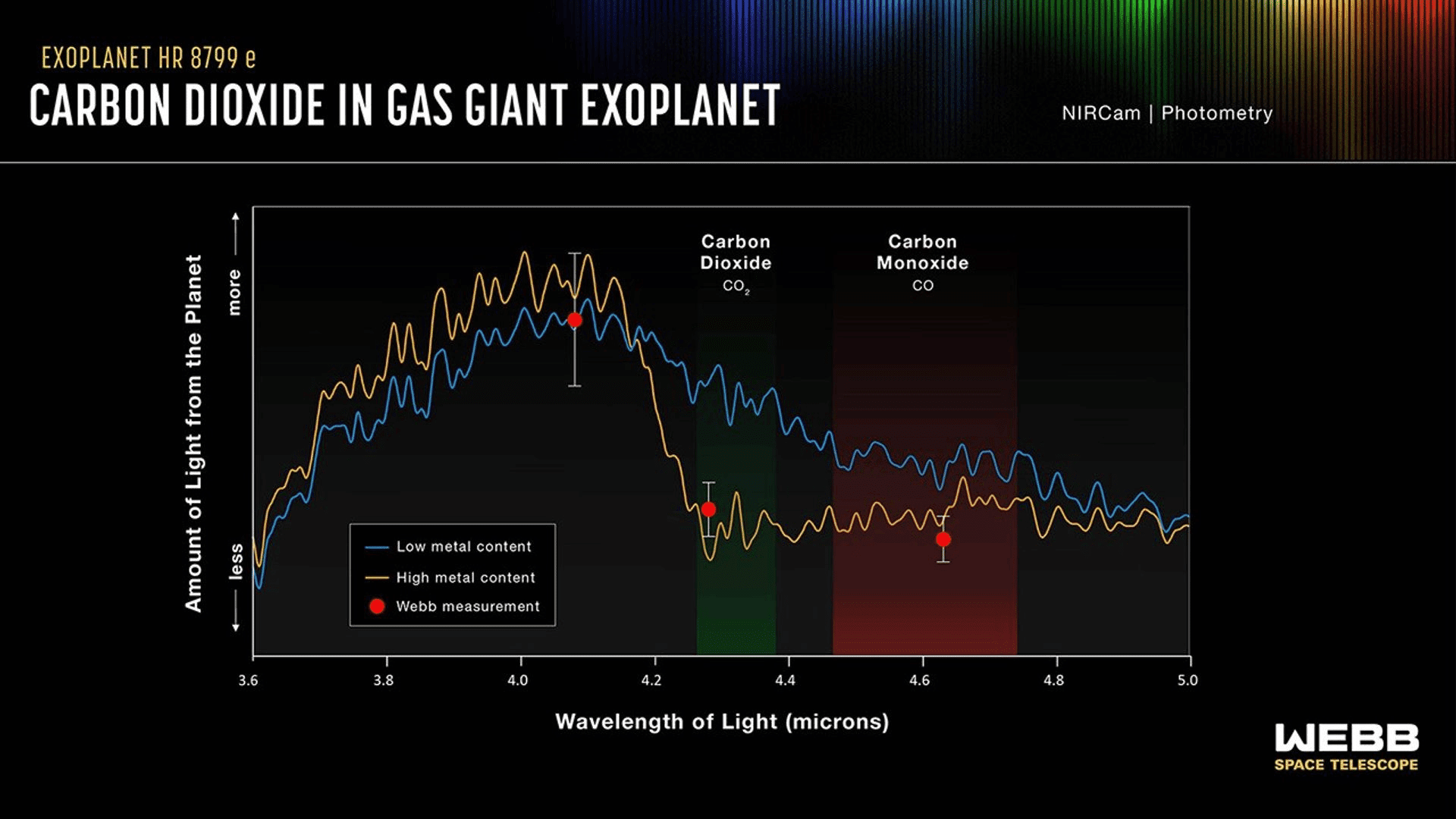

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has captured direct images of gas giant exoplanets within the HR 8799 planet system, finding that the planets are rich in carbon dioxide gas.

Exoplanet Observations

The system is located approximately 130 light-years away and has been a focus for researchers studying planet formation. The new discovery provides evidence that the system’s four giant planets formed from core accretion, similar to Jupiter and Saturn in our solar system.

These findings also showcased the James Webb Space Telescope’s ability to infer the chemistry of exoplanet atmospheres solely through imaging. This technique works alongside Webb’s powerful spectroscopic instruments to resolve the atmospheric composition.

“By spotting these strong carbon dioxide features, we have shown there is a sizable fraction of heavier elements, like carbon, oxygen, and iron, in these planets’ atmospheres,” said William Balmer, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “Given what we know about the star they orbit, that likely indicates they formed via core accretion, which is an exciting conclusion for planets that we can directly see.”

HR 8799 is a young system of approximately 30 million years old, a small fraction of our solar system’s 4.6 billion years. As the system is younger, the planets are still hot from their formation and emit large amounts of infrared light. This gives scientists crucial data on how these types of systems form.

James Webb Space Telescope Imaging

Giant planets typically form in one of two ways: by gradually building solid cores with heavier elements that attract gas or when particles of gas rapidly coalesce into massive objects from a young star’s cooling disk. The first process is called core acceleration, and the second is called disk instability. If scientists can determine which formation model is most common, it may give them the ability to distinguish between planets they find in other systems.

“Our hope with this kind of research is to understand our own solar system, life, and ourselves in the comparison to other exoplanetary systems, so we can contextualize our existence,” Balmer said. “We want to take pictures of other solar systems and see how they’re similar or different when compared to ours. From there, we can try to get a sense of how weird our solar system really is—or how normal.”

The new images were made possible by Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) coronagraph, which blocks light from bright stars to reveal otherwise hidden details. This allowed the team to search for infrared light emitted by the planets in wavelengths that are absorbed by specific gases, finding that HR8799 contained more heavy elements than previously believed.

The results of the study were published in The Astrophysical Journal.