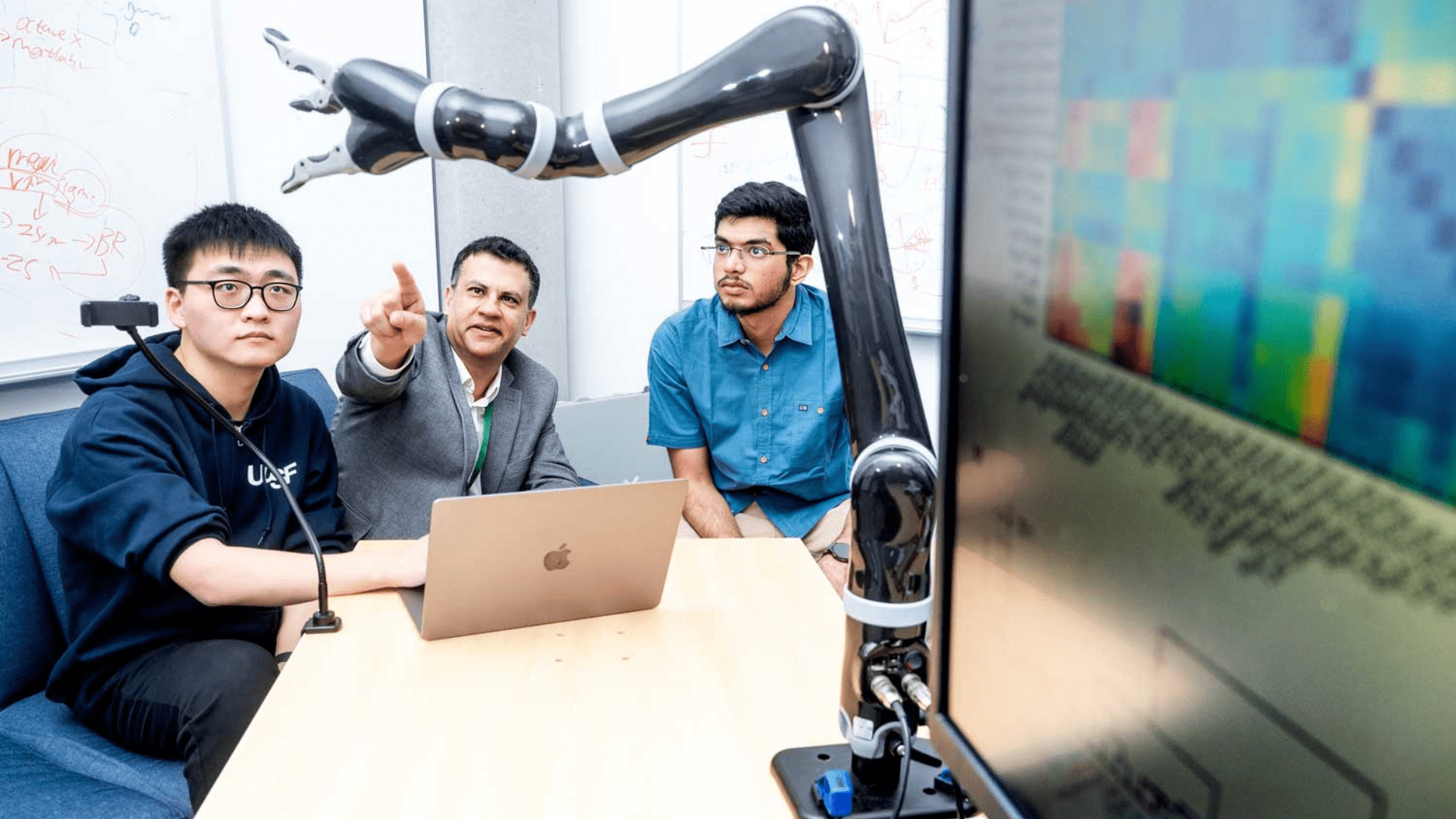

Researchers at UC San Francisco used a brain chip to enable a man with paralysis to control a robotic arm for seven months straight. The chip takes signals from the brain via a computer and sends them to the robotic arm. Until this breakthrough, the brain-computer interface (BCI), which researchers used on the paralyzed man, had only worked for a day or two.

BCI and AI

The BCI heavily utilizes an artificial intelligence model that learns repetitive movements—or in this case, the researchers say, an imagined movement—and learns to do it in a more polished way.

“This blending of learning between humans and AI is the next phase for these brain-computer interfaces,” said neurologist and professor of neurology Karunesh Ganguly. “It’s what we need to achieve sophisticated, lifelike function.”

According to the researchers, the key was discovering how activity shifted in the brain day to day as the study participant repeated imagined movements. Once the AI was programmed to account for all of those shifts, the technology was capable of running for months.

Ganguly studied how brain activity impacted specific movements in animals but found out the patterns changed day to day as the animals learned. He suspected the same thing was happening with humans, ultimately leading to the BCI quickly losing its ability to learn and recognize patterns.

Ganguly and neurology researcher Nikhilesh Natraj implanted sensors on the surface of the brain of the study participant, who had been paralyzed by a stroke, to pick up on movements he imagined. The participant could not speak. The researchers analyzed the changes in the participant’s brain patterns by asking him to imagine moving different body parts, such as his hands, feet, and head. Although he couldn’t move, the brain signals could still produce the signals.

Operating the Robotic Arm

The researchers started slow, only asking the participant to imagine moving his fingers, thumbs, and hands over the course of two weeks while the sensors trained the AI on the movements. Then, the participant tried to move the robotic arm, but the movements weren’t very precise. As a result, the researchers switched to a virtual robotic arm, eventually getting the participant to control it.

Once the participant started practicing the real robot arm, it reportedly only took a few training sessions to transfer the virtual skills into the real world. Eventually, the participant could pick up blocks and move them around to different locations. Then, he was able to open a cabinet, take a cup out, and hold it under a water dispenser.

After a few months, the participant could still control the robot arm, only needing a quick “tune-up.” This research marks a huge milestone in enabling people who are paralyzed to once again be able to feed themselves or get themselves a glass of water—things that may not mean much but are life-changing.

Ganguly said, “I’m very confident that we’ve learned how to build the system now, and that we can make this work.”