Researchers at the University of Copenhagen are developing a 100% biodegradable barley plastic. The new plastic decomposes in a fraction of the time it takes traditional plastic to break down. As plastic continues to riddle the Earth, the developers hope their invention could be a solution.

Impact of Plastic

There are many benefits to plastic. For example, it’s durable, cheap, and versatile. That’s why we see it in packaging, materials, and almost everything else. However, there are just as many downsides to plastic. There are excessive amounts of plastic floating in our oceans and on the side of the road. It contaminates nature and is difficult to recycle. According to the University of Copenhagen, plastic production produces more CO2 emissions than all air traffic combined.

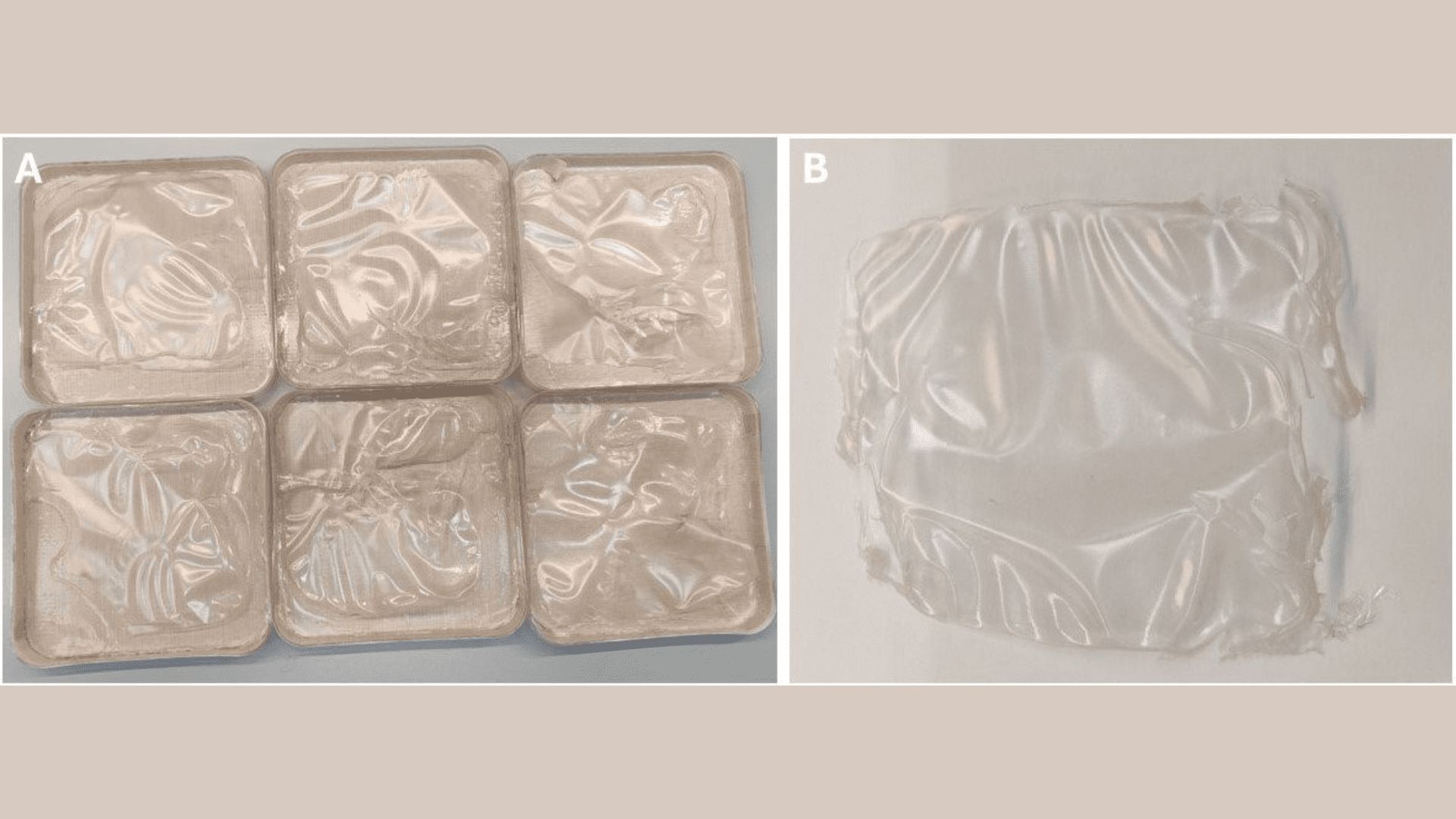

This is why researchers at the University wanted to invent a new plastic. And they did. The new material is made of modified starch that completely decomposes in two months. This new plastic includes natural plant material from crops and can be used for food packaging.

“We have an enormous problem with our plastic waste that recycling seems incapable of solving,” said Professor Andreas Blennow. “Therefore, we’ve developed a new type of bioplastic that is stronger and can better withstand water than current bioplastics.” Professor Blennow is part of the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, the department developing the new material. He said, “At the same time, our material is one hundred percent biodegradable and can be converted into compost by microorganisms if it ends up somewhere other than a bin.”

A New Bioplastic

Bioplastics aren’t a new concept, but Professor Blennow says the name is misleading. Only a limited amount of bioplastic materials are degradable, and they break down only in special conditions in industrial composting plants.

Explore Tomorrow's World from your inbox

Get the latest science, technology, and sustainability content delivered to your inbox.

I understand that by providing my email address, I agree to receive emails from Tomorrow's World Today. I understand that I may opt out of receiving such communications at any time.

“I don’t find the name suitable because the most common types of bioplastics don’t break down that easily if tossed into nature,” said Blennow. “The process can take many years and some of it continues to pollute as microplastic.” Bioplastics need specialized facilities to break down. Blennow said, “And even then, a very limited part of them can be recycled, with the rest ending up as waste.”

The so-called biocomposite contains several ingredients that decompose naturally. Its main ingredients are amylose and cellulose, which are common across the plant kingdom. For example, amylose is extracted from many crops, including corn, potatoes, and barley.

“Amylose and cellulose form long, strong molecular chains,” said Blennow. “Combining them has allowed us to create a durable, flexible material that has the potential to be used for shopping bags and the packaging of goods that we now wrap in plastic.” So far, the researchers have only developed prototypes in the lab. However, professor Blennow says getting production started in Denmark and many other places is relatively easy.

“The entire production chain of amylose-rich starch already exists. Indeed, millions of tons of pure potato and corn starch are produced every year and used by the food industry and elsewhere,” said Blennow, “Therefore, easy access to the majority of our ingredients is guaranteed for the large-scale production of this material.”

Reducing Plastic

The researchers are processing a patent application. Once approved, it could pave the way for production of the new biocomposite material. Despite the large sum of money devoted to sorting the new plastic, Blennow doesn’t believe it will be successful. He says it is a transitional technology until we say farewell to fossil-based plastics.

The researcher said, “Recycling plastic efficiently is anything but straightforward.” There are different ways each plastic is sorted because of the major differences in each plastic. This means the process needs to be done without any contaminants ending up in recycled plastics. He believes countries and consumers must sort their plastic. “This is a massive task that I don’t see us succeeding at,” said Blennow. “Instead, we should rethink things in terms of utilizing new materials that perform like plastic, but don’t pollute the planet.”