Researchers at Japan’s Tohoku University and Nagaoka College conducted a test to observe the decision-making prowess of a cord-forming fungus known as Phanerochaete velutina.

Fungi are unique creatures because they don’t have brains but display clear signs of decision-making and communication. According to a new study published in Fungal Ecology, fungi can recognize different spatial arrangements of wood and adapt accordingly.

More visible fungi, such as mushrooms, are scratching the surface of a vast network of underground threads called mycelium. These webs can pass information through a system that can go on for miles, but the growth patterns appear to be calculated.

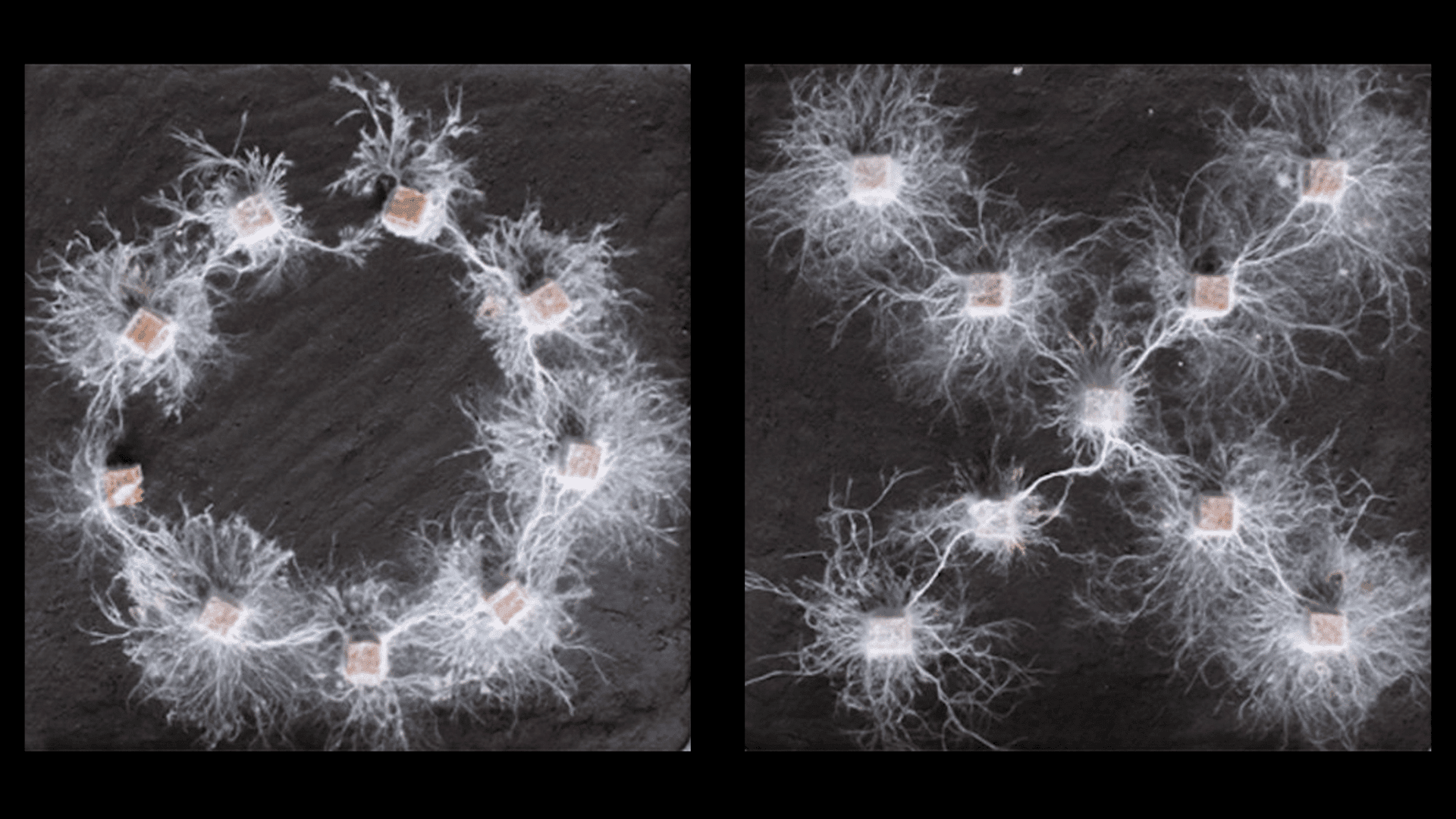

To showcase this, researchers set up two 24-cm-wide (9.44-in-wide) square dirt environments and soaked decaying wood blocks for 42 days in a solution containing P. velutina spores. They then placed the blocks in either a circular or cross-shaped arrangement inside the box and let the fungi grow for 116 days.

At the beginning of the experiment, the mycelium grew outward around each block for 13 days without connecting to each other. About a month later, however, both arrangements displayed extremely tangled fungi webs stretching between every wood sample.

By day 116, each fungal network had organized itself into much more deliberate, clearly defined pathways. In the circle setting, P. velutina displayed uniform connectivity, growing outward but barely growing into the ring’s interior. Meanwhile, the cross fungi extended much further from its four outermost blocks.

The theory is that the mycelial network communicated in the circular environment and determined that growing into an occupied area was of little advantage. The team thinks the four exterior posts’ growth areas served as “outposts” for foraging missions in the cross scenario.

These experiments suggest that the organisms communicated through the mycelial networks and decided to grow according to the environmental layout.

“You’d be surprised at just how much fungi are capable of. They have memories, they learn, and they can make decisions,” Yu Fukasawa, a study co-author at Tohoku University, said in the paper’s announcement on October 8th. “Quite frankly, the differences in how they solve problems compared to humans is mind-blowing.”