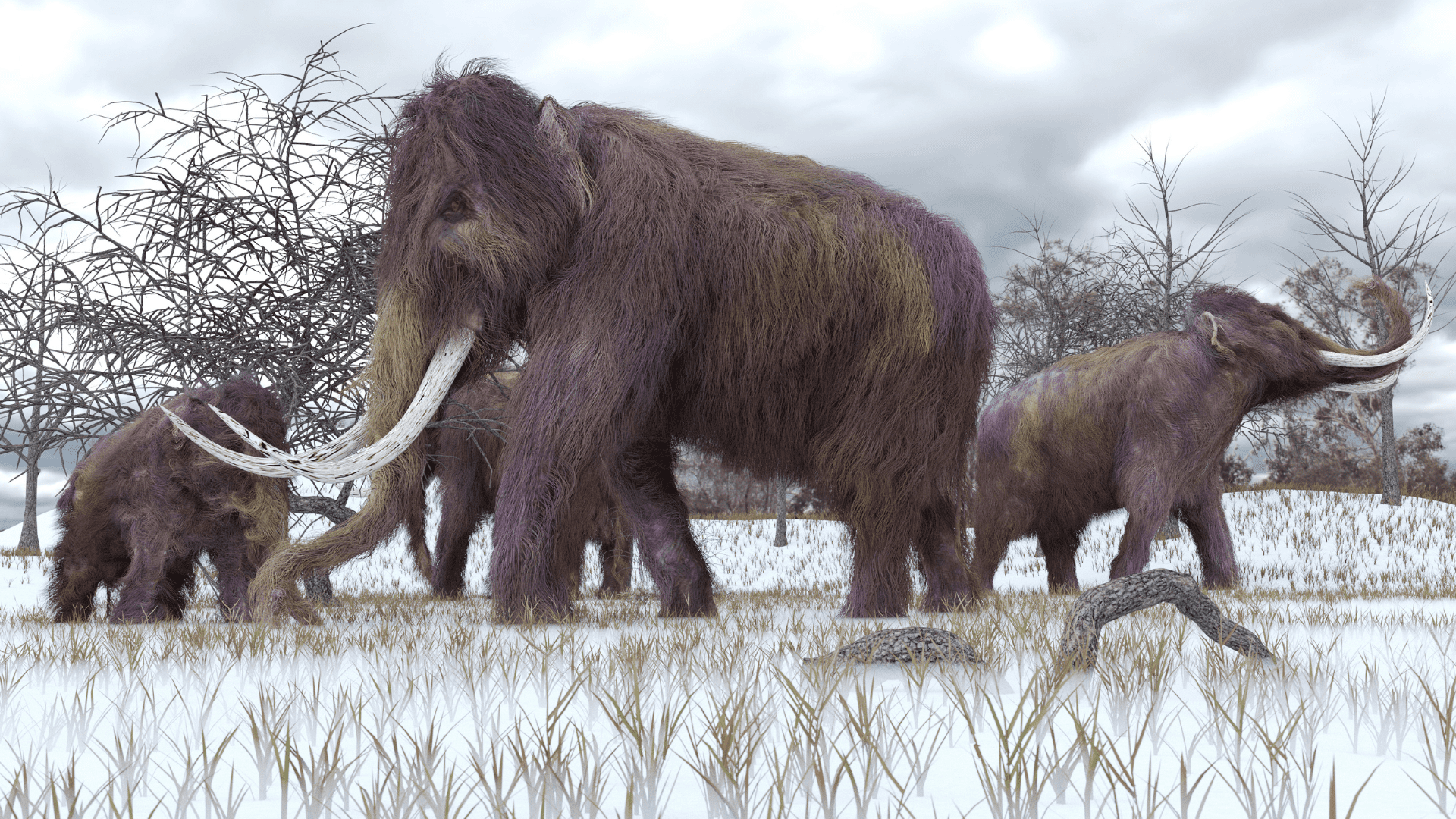

After analyzing scratch marks on a 39,000-year-old Woolly Mammoth, researchers have uncovered the earliest known evidence of human presence in the Arctic.

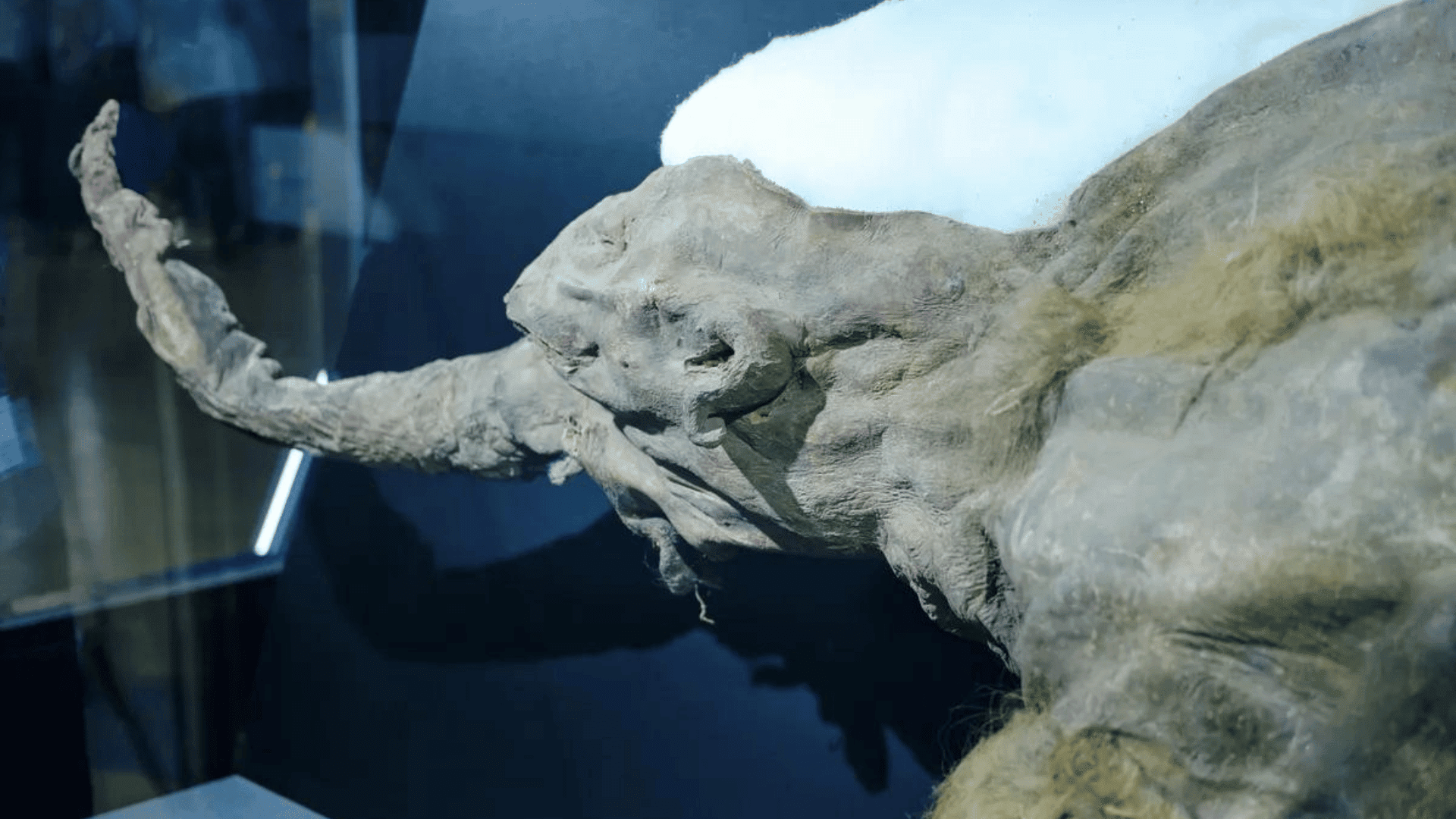

The specimen was originally unearthed in 2010 in Northern Siberia and was given the name Yuka. The series of marks on Yuka’s body are the subject of a recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science as there is speculation regarding whether the markings could have been inflicted by humans.

The scratches along the animal’s eye sockets and spine stand out against other traces attributed to animal activity 39,000 years ago. After a series of experiments, researchers determined that prehistoric humans were responsible for the marks. This makes Yuka particularly significant as archaeological records suggest that evidence of humans in the Arctic fades after 35,000 years.

According to Interesting Engineering, previous studies have suggested that mammoth hunting may have allowed people to survive and thrive across the northernmost Arctic Siberia. Thus, “affirmative evidence exists of single target hunts for adult mammoth,” the recent study posits but calls them isolated events.

Regarding Yuka, one theory suggests that cave lions may be responsible for the claw marks on the legs and underside of the body. Though damage to the mammoth’s fur and missing skin pieces may indicate an animal attack, there is a significant tendon that was methodically cut with precise incisions along the spine and eye sockets.

As the clean cuts contrast the animal markings, researchers investigated this further using the types of tools that existed at the time. According to IFL Science, researchers performed traceological analysis on cowhide and mammoth samples to identify the origins of these marks.

“The results of the experimental work have shown that they have certain traceological characteristics that clearly distinguish them from injuries committed by animals,” the study stated.

Using ancient stone blades and metal knives, the researchers were able to match the cuts on the animal to incisions made with a flint blade. As the timing of the cuts suggests they were made close to the animal’s death, the study affirms that humans occupied the Arctic as far back as 39,000 years ago.