When you think of a farm, you might picture vast fields of crops in the countryside. You imagine long stretches of land that could never thrive in an urban environment, much less be able to be grown on the move.

That image may soon change.

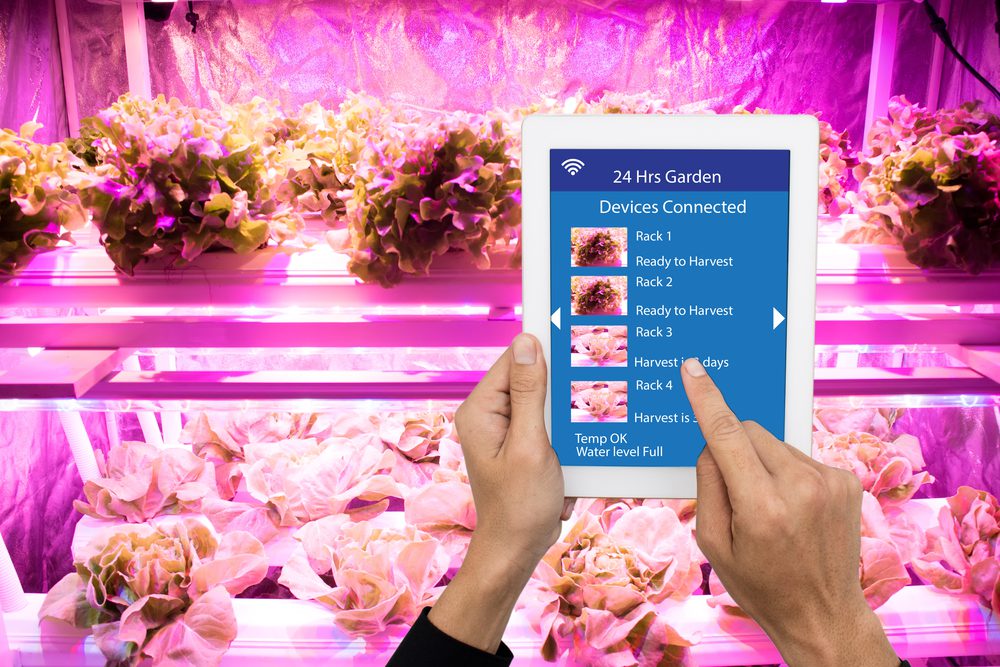

Vertical farming is exactly what it sounds like: food (usually produce) grown in a vertical fashion, either stacked on top of one another and/or on various vertical surfaces. They can even be grown on the sides of skyscrapers or inside shipping containers.

While the idea is not new- records indicate a prototype called the “Tower Hydroponicums” existed in Armenia in the 1950s- it wasn’t until 2012 that the practice was used commercially by a company called Sky Green Farms in Singapore. Thanks to technology like grow lights (artificial lights meant to mimic sunlight) and precision agriculture (which uses infrared lights to read the vitality and viability of crops), the process of vertical farming is more accessible than ever.

That being said, it’s still not widely used, due to a slew of drawbacks. From an economic standpoint, it’s less likely to turn a profit, because of both the cost of building a space for the farm (or buying the exterior of an office building) and the increased cost of powering, lighting, and heating. There’s also the question of pollution, as excess CO2 is needed to ensure plants have the proper nutrients. In cities that already release a large amount of toxins in the air, it could put residents at risk, especially those with health issues.

There’s also the question of energy use. While sunlight is naturally free and consistently provided, the angle the sun’s rays hit the side of a building would result in less sun reaching the plants than ones planted in a traditional, flat-ground farm. As a result, artificial light would have to be used to make up for the lack of natural light, which would create an even bigger carbon footprint than traditional farms.

There’s also the question of energy use. While sunlight is naturally free and consistently provided, the angle the sun’s rays hit the side of a building would result in less sun reaching the plants than ones planted in a traditional, flat-ground farm. As a result, artificial light would have to be used to make up for the lack of natural light, which would create an even bigger carbon footprint than traditional farms.

It may sound as if vertical farming is an interesting, but ultimately unbeneficial idea. While there are the aforementioned downsides, there are several pros, mostly related to the future of our planet. According to a report put out by The Institute of Horticulture, the human population may increase by nearly 3 billion by the year 2050. Because vertical farming can result in higher crop numbers, some crops–such as strawberries–are multiplied by a factor of 30 compared to traditional farming. Vertical farming could help prevent this new population boom from starving.

Furthermore, as vertical farming uses less land than traditional, it would prevent overcrowding and may even slow/prevent the extinction of animals such as the wood mouse, which are currently in danger during harvesting.

It would also greatly benefit the cities where vertical farms would be built. As lack of food security is such a big part of poverty, having easy access to fresh produce would help millions of humans who would not have money to buy it otherwise. It would also promote urban growth, offering job opportunities and spurring the repair of existing buildings, rather than building new ones. Access to produce would allow people to eat healthier, resulting in lower obesity and heart disease rates. Deforestation and desertification rates would go down, and as the crops are grown closer to urban centers, the carbon footprint wouldn’t be as high.

So, what does the future of vertical farming look like? Is it on the verge of being the next big thing, or is it little more than a pipe dream? It’s still a bit iffy, but things are looking promising.

In late 2017, indoor farming company Plenty announced their plans to open a facility near Seattle, their first outside of south San Francisco and Wyoming. The farm will be 100,000 square feet and will utilize vertical farming in the form of 20-foot towers to house the produce. Investors for Plenty include the founder of Amazon, Jeff Bezos; SoftBank; and Eric Schmidt, chairman of Alphabet, Inc.

Matt Barnard, founder of Plenty, recently said in an interview with GeekWire that Seattle was the perfect place to begin expanding. “As we looked at the West Coast, Seattle was the best example of a large community of people who really don’t have much access to any fresh fruits or vegetables grown locally.” Considering the region’s emphasis on healthy eating, it made establishing the farm there an easy decision.

Barnard’s long-term goal for the company is to build a farm similar to the one in Seattle in every city with more than one million residents. That would be roughly 500 vertical farms–no easy feat for any company. But Plenty is confident in its abilities, claiming “it can build a farm in 30 days and pay investors back in three to five years.” The Seattle farm plans to start distributing produce sometime this year.

Barnard’s long-term goal for the company is to build a farm similar to the one in Seattle in every city with more than one million residents. That would be roughly 500 vertical farms–no easy feat for any company. But Plenty is confident in its abilities, claiming “it can build a farm in 30 days and pay investors back in three to five years.” The Seattle farm plans to start distributing produce sometime this year.

Arguably the most famous example of vertical farming would be the greenhouses at EPCOT in Walt Disney World, seen on the “Living with the Lands” attraction. These greenhouses aren’t just using tower farms, however, as hydroponics and other agricultural technology are also at play. It’s also one of the only places you can see tomatoes and pumpkins grown to be in the shape of Mickey Mouse heads, which is probably more interesting to the kids on the ride. Walt Disney World also purchases some of its produce from “The GreenHouse,” located in Orlando.

Also already making waves is RoBotany. Co-founded in 2016 by Carnegie Mellon alum Austin Webb, RoBotany (as the name implies) utilizes both vertical farming techniques and robots to grow their produce. Their first farm, a scant 50 square feet, was able to produce roughly a pound of microgreens per day. Now they have 2,000 sq feet of farm, capable of making 40 times the amount of food in the same amount of time. They hope to eventually convert about half of their facility- the former Follansbee Steel Corporation building- into farm towers. This would result in 2,000 pounds of produce each day, easily feeding a portion of the city.

As-is, they’re already starting to feed the public. The Whole Foods in Upper St. Clair, PA sells arugula and cilantro grown by RoBotany under the name Pure Sky Farms. They hope to begin providing to other retailers and restaurants soon, once production increases. Their current farm also grows micro-kale and spinach, as well as herbs. In an interview with the Pittsburgh Tribune, Webb expressed interest in eventually expanding into other fruits and vegetables. “You can’t just feed the world lettuce,” he explained.

Brac Webb, Austin’s brother and another member of the RoBotany team, emphasizes the importance of vertical farming in today’s world. With the growing population and shrinking viable farm land, finding new ways to provide food is essential. “This is probably one of the first problems humanity needs to solve,” he said. Considering the drawbacks of traditional farming and how many vertical farming groups don’t seem to utilize their space properly, it makes their claim of using 95% less water than outdoor farming all the more impressive.

It might just be impressive enough to change how we see farming forever.