Scientists at the University of Oxford are designing OvarianVax, a vaccine that they hope teaches the immune system to recognize and attack the earliest stages of ovarian cancer. The team will receive up to £600,000 ($786,390) for the study over the next three years to support lab research into the vaccine.

The Study

The Director of the university’s ovarian cancer cell laboratory, Prof. Ahmed Ahmed, said there is still a long way to go, but they are “optimistic.”

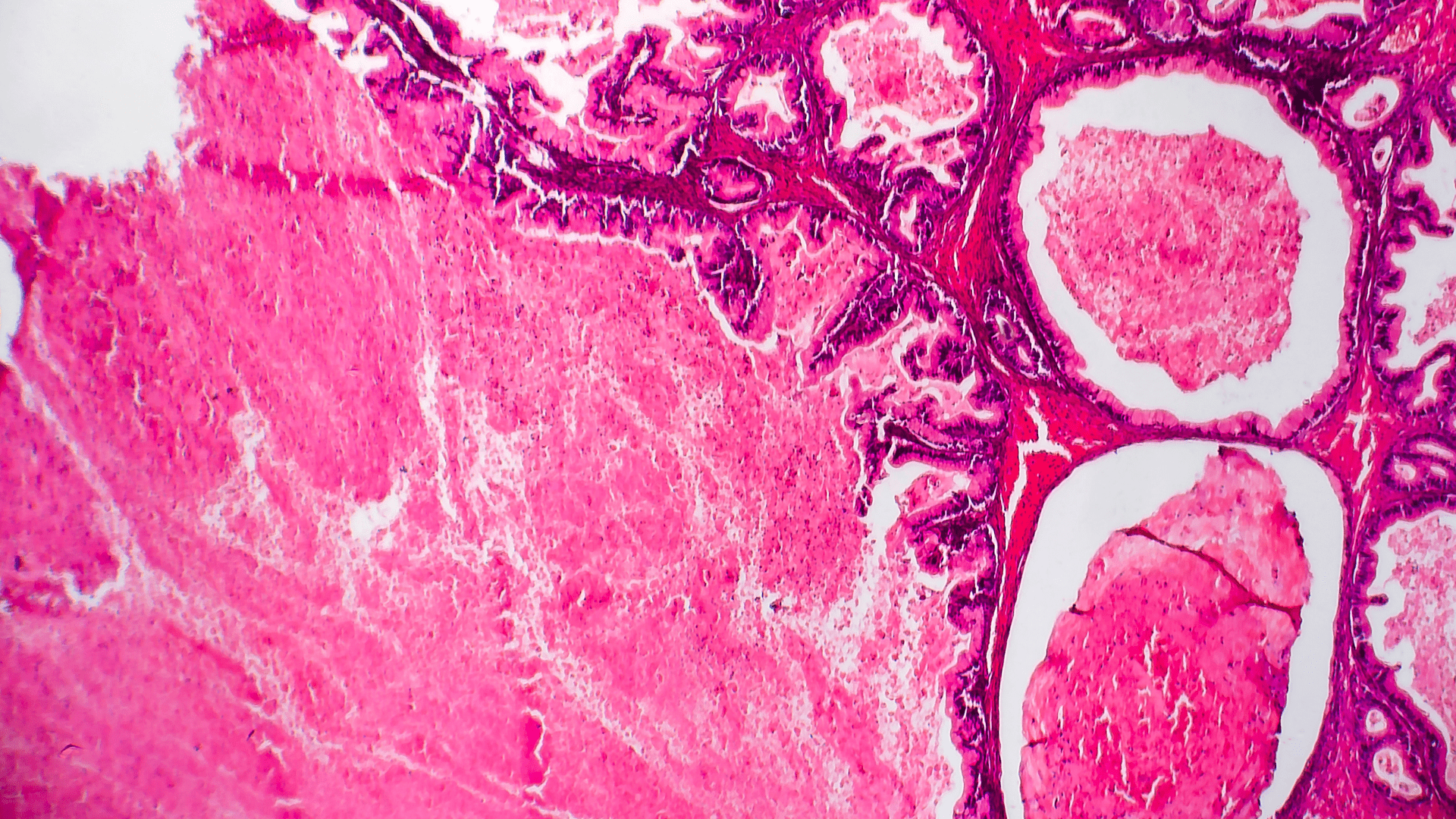

First, the scientists will create the vaccine in the lab, hoping to train the immune system to recognize the proteins on the surface of ovarian cancer, known as tumor-associated antigens. Then, they will test the vaccine in patients with the disease. Prof. Ahmed said, “The idea is, if you give the vaccine, these tiny tumors will hopefully either reduce, shrink really significantly, or disappear.”

The next stage will include women with genetic mutations who are more likely to get the disease and women without the known disease to see if the vaccine is successful at preventing ovarian cancer.

“Teaching the immune system to recognize the very early signs of cancer is a tough challenge,” Ahmed said. “But we now have highly sophisticated tools which give us real insights into how the immune system recognizes ovarian cancer.”

Ovarian Cancer

According to Oxford University, there are 7,500 new ovarian cancer cases every year in the UK. Oxford says it is the 6th most common cancer in women. The American Cancer Society estimates about 19,680 women in the U.S. will receive a new diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 2024.

There is no screening test for ovarian cancer, and it is often diagnosed late because the symptoms, like bloating and loss of appetite, can be vague. Genetic mutations put some women at higher risk for the disease, and women with certain kinds of genetic mutations are advised to get their ovaries removed by the age of 35.

Researchers remain positive about the vaccine, saying if it is successful, the vaccine could eventually eliminate a woman’s need to remove their ovaries. Dr. David Crosby, head of prevention and early detection research at Cancer Research UK, said it will be “many years” before any potential vaccine is ready for wider use.

He said, “At this stage, scientists are testing the best components to include in the vaccine by first trialing it in the lab with samples taken from ovarian cancer patients.”