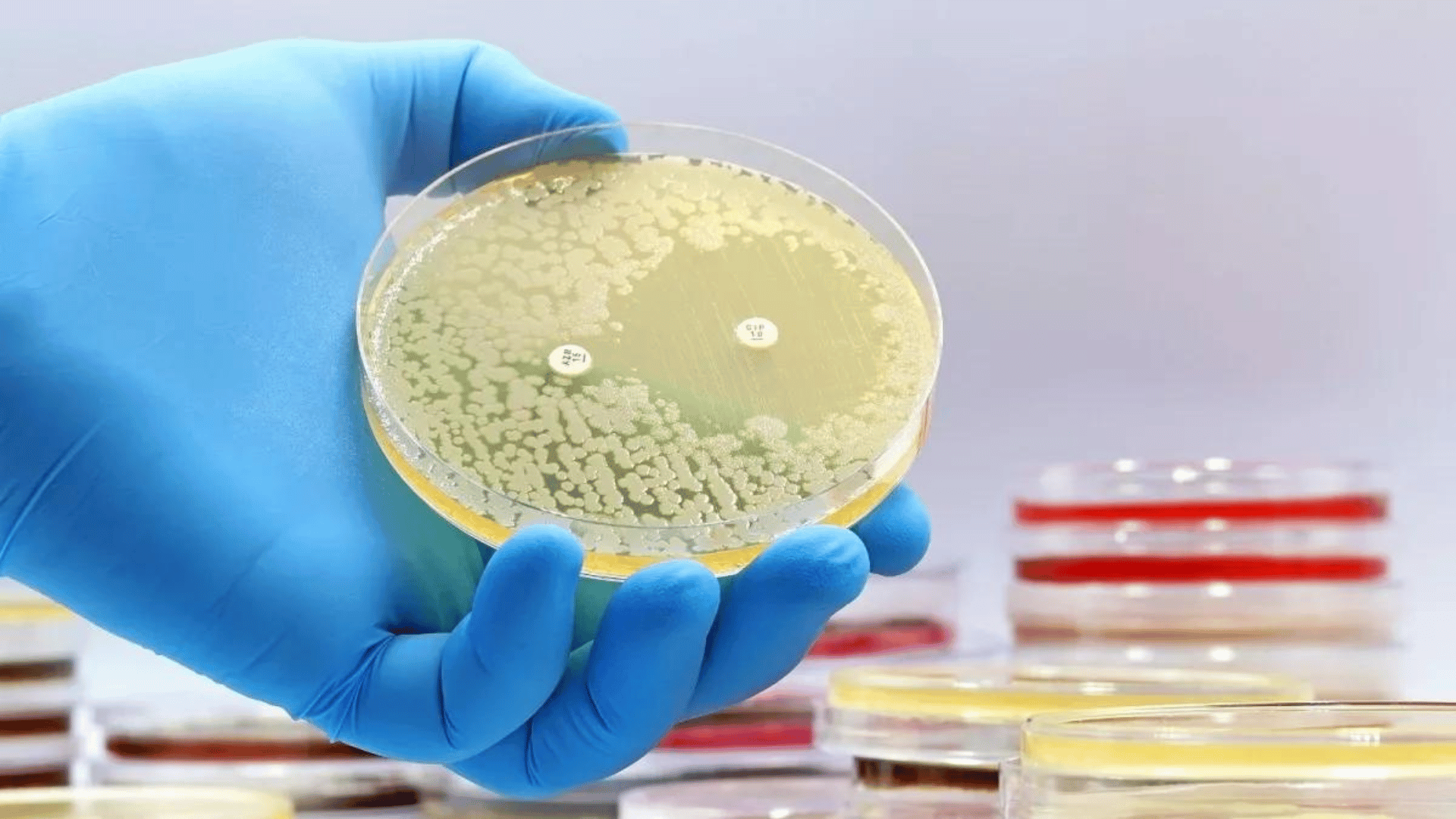

AI was used to help discover the first new class of antibiotics in 60 years. The antibiotic is a new compound that can kill the drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria that kills thousands worldwide each year.

MRSA infections can range from mild skin infections to more severe conditions such as pneumonia and bloodstream infections. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), almost 150,000 MRSA infections occur every year in the European Union while almost 35,000 people die annually in the bloc from antimicrobial-resistant infections.

The research team behind the project used a deep-learning model to predict the activity and toxicity of the new compound. Deep learning involves the use of artificial neural networks to automatically learn and represent features from data without explicit programming.

The use of deep learning is being increasingly applied in drug discovery. It’s used to accelerate the drug development process by rapidly identifying potential drug candidates and predicting their components.

In this case, the MIT team of researchers trained an extensively enlarged deep learning model using expanded datasets. Approximately 39,000 compounds were evaluated for their antibiotic activity against the MSRA to create the training data. The resulting data and details regarding the chemical structures of the compounds were input into the model.

“What we set out to do in this study was to open the black box. These models consist of very large numbers of calculations that mimic neural connections, and no one really knows what’s going on underneath the hood,” said Felix Wong, a postdoc at MIT and Harvard and one of the study’s lead authors.

Three additional deep-learning models were employed to help refine the selection of potential drugs. These models were trained to assess the toxicity of compounds on three types of human cells.

Approximately 12 million commercially available compounds were screened using this set of models. The models identified compounds from five different classes that exhibited predicted activity against MRSA.

The researchers then acquired around 280 of these compounds and conducted tests against MRSA in a laboratory setting. The tests led the team to identify two promising antibiotic candidates. In trials involving two mouse models (one for MRSA skin infection and another for MRSA systemic infection), each of these compounds reduced the MRSA population by a factor of 10.

“The insight here was that we could see what was being learned by the models to make their predictions that certain molecules would make for good antibiotics,” stated James Collins, professor of Medical Engineering and Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and one of the study’s authors. “Our work provides a framework that is time-efficient, resource-efficient, and mechanistically insightful, from a chemical-structure standpoint, in ways that we haven’t had to date.”