The Icelandic Biennial “Sequences” is an art exhibition themed around the concept of darkness, which is a staple of the region and culture.

The curators of the artist-run Icelandic Biennial selected the title “Can’t See” for its 11th edition, which is on view at several locations until November 26th. The curators—Marika Agu, Maria Arusoo, Kaarin Kivirähk, and Sten Ojavee—are part of a collective from the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art.

“We have all these stories about mythological creatures, mysterious events, and hidden people, which is all to do with the brutality of living here,” stated Sunna Ástþórsdóttir, director of the Living Art Museum, which is a co-founder institution of the biennial.

Using the concept of darkness as its center point, the show showcases both the life forms that humanity can’t perceive as well as issues that we blindly refuse to recognize.

“The title applies to today’s world, with the ungraspable climate catastrophe on its way, but also war in Ukraine and pandemics, so darkness just seems very current,” said Kivirähk. “But it can also be read as the possibility that you might be using your imagination if you can’t see, so the theme embraces both doom and celebration.”

The biennial is divided into four chapters – “Subterranean,” “Water,” “Soil,” and “Metaphysical Realm,” with exhibitions dedicated to these themes on show at four Reykjavik institutions. The exhibition features more than 50 Icelandic and international artists, including Nigerian-American artists Precious Okoyomon and Dozie Kanu, as well as Edith Karlson, who will represent Estonia at the 2024 Venice Biennale.

The exhibition combines new commissions with works from museum collections. For example, it pairs landscape paintings by Iceland’s art grandee Jóhannes Kjarval (1885-1972) with Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir’s multidisciplinary works based around Surtsey, a volcanic island that erupted off Iceland in 1963. This section also includes her cast of what is believed to be the earliest fossilized human footprint on Earth.

“I have loved Kjarval’s paintings since I was a child, but it hadn’t occurred to me that our works would coincide,” said Ólafsdóttir. “I love all the details in his paintings. They somehow resonated with the tiny particles of seaborne waste embedded in the footprint, so it was an unexpected but happy encounter.”

Many artworks included in the exhibition draw inspiration from Iceland’s geography and vivid folklore traditions. For example, in the “Subterranean” section, Finland-based artist Monika Czyżyk covered windows with symbols and faces related to creatures she saw in stones, mountains, and rivers using a variety of earthy clay tones she found in the Icelandic wilderness.

“It feels like we are portraying hidden, speculative worlds, inspired by our surroundings, science, ecology and heliobiology,” Czyżyk stated.

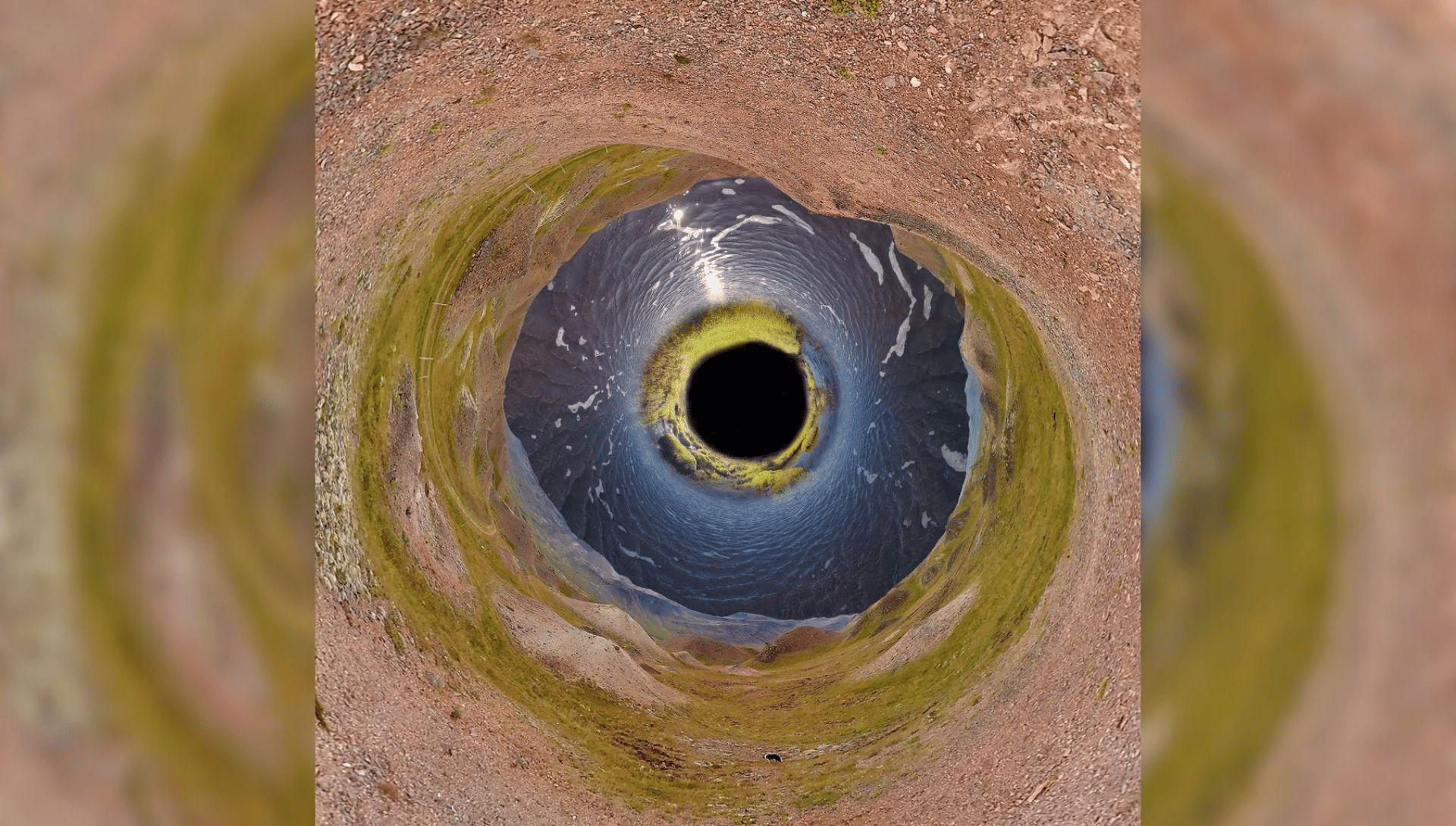

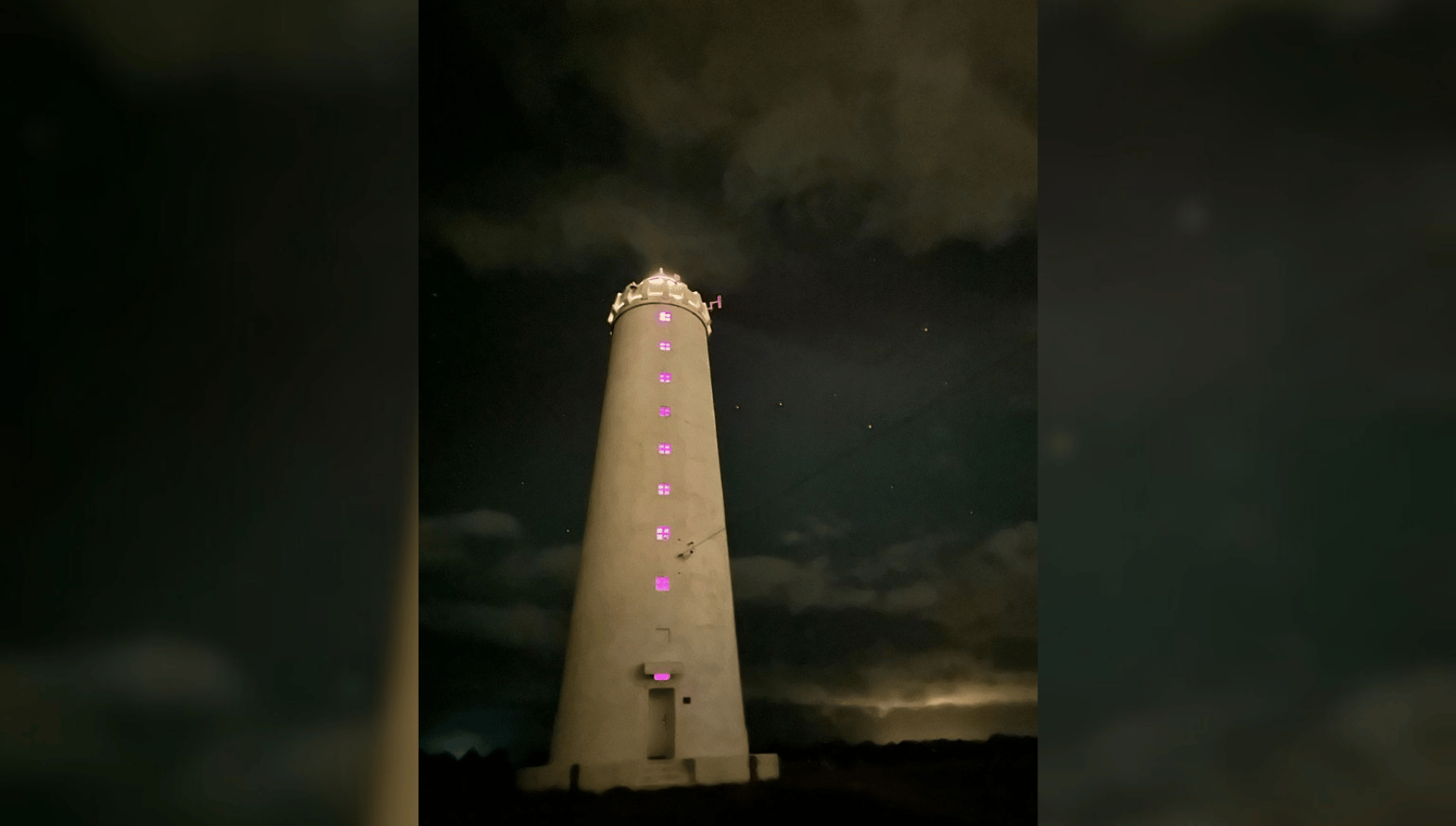

Other pieces of note include the exhibition titled Fragmented sky – wind – fly giving presence to wind (2023), which is a collaboration between artists Okoyomon and Kanu and features a wind installation in a lighthouse. There is also a piece titled Black Whole (2023) by Hrund Atladóttir which features a video and AI portal into nature.

The exhibition centers around the idea of removing humans from the conversation and focusing on the landscape and natural world of Iceland.

“We tried to limit the human narration and human representation in the exhibition, to allow ourselves to imagine the world around us through the senses of a variety of species,” explained curator Sten Ojavee.