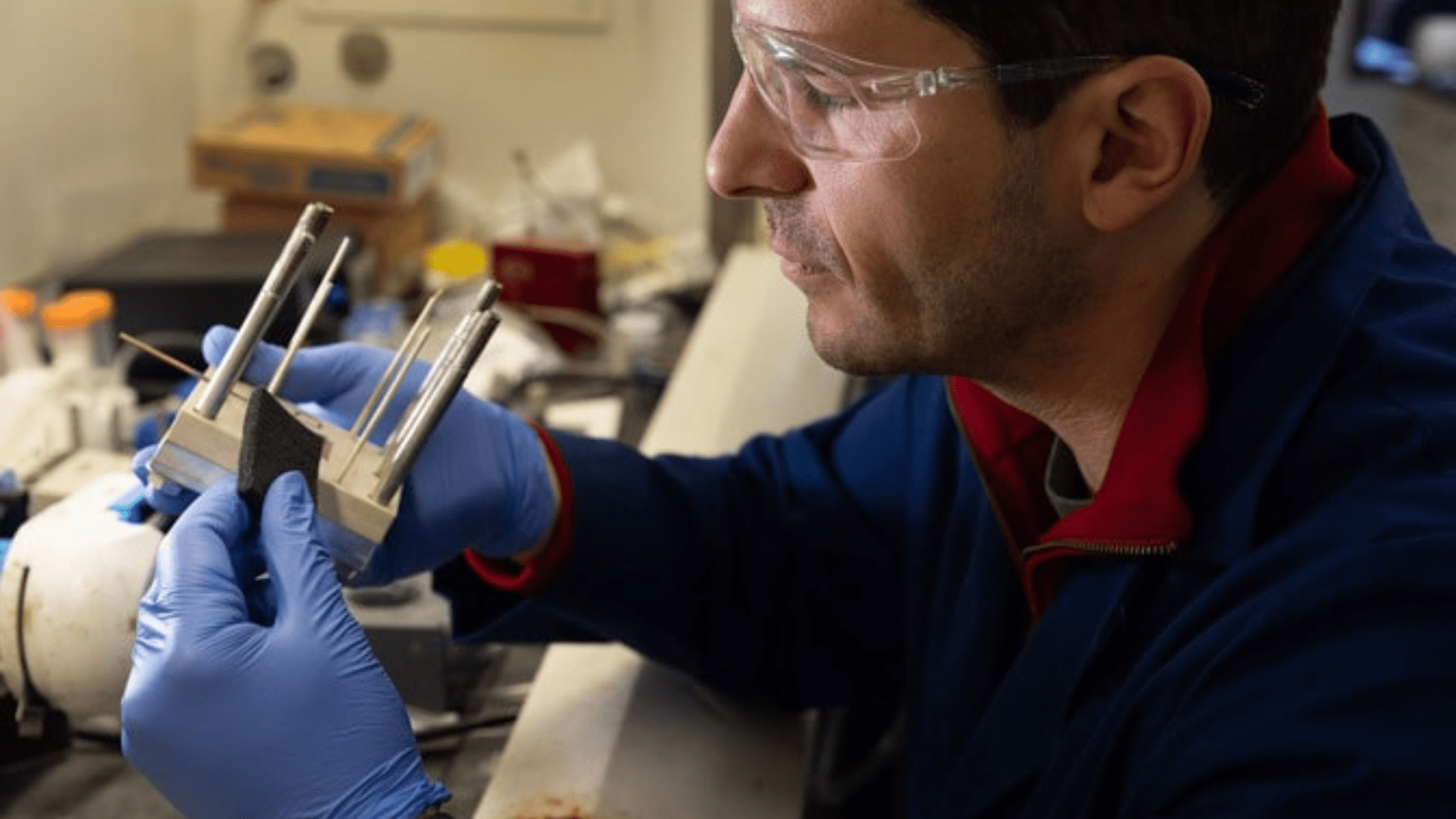

Engineers from the University of Michigan and Rice University believe water desalination plants (plants that remove salt from water) could replace harsh chemicals with new carbon cloth electrodes. The technology is a new way to remove boron from seawater, an important step in turning saltwater into safe, drinkable water.

Drinkable Water Device

“Most reverse osmosis membranes don’t remove very much boron, so desalination plants typically have to do some post-treatment to get rid of the boron, which can be expensive,” said Jovan Kamcev, U-M assistant professor and a co-corresponding author of the study. “We developed a new technology that’s fairly scalable and can remove boron in an energy-efficient way compared to some of the conventional technologies.”

Boron, a natural element in seawater, can become a harmful contaminant in drinking water when it bypasses standard salt-removal filters. Seawater contains boron levels roughly double the World Health Organization’s maximum safe limit for drinking water. This is five to twelve times higher than what many agricultural plants can tolerate.

In ocean water, boron exists as neutral boric acid. It passes through reverse osmosis membranes that typically remove salt by repelling ions. To avoid this, desalination plants normally add a base to treated water, which causes the acid to become negatively charged. Another reverse osmosis stage removes the newly charged boron, and the base is neutralized by adding acid. However, researchers say these extra steps are costly.

Weiyi Pan is a postdoctoral researcher at Rice University and and co-first author of the study. She said, “Our device reduces the chemical and energy demands of seawater desalination, significantly enhancing environmental sustainability and cutting costs by up to 15 percent, or around 20 cents per cubic meter of treated water.”

“Our study presents a versatile platform that leverages pH changes that could transform other contaminants, such as arsenic, into easily removable forms,” said Menachem Elimelech, the Nancy and Clint Carlson Professor at Rice University and a co-corresponding author of the study.

“Additionally, the functional groups on the electrode can be adjusted to specifically bind with different contaminants, facilitating energy-efficient water treatment,” Elimelech said.