According to researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, a geological phenomenon called “cratonic thinning” could be causing the underside of North America to melt into the Earth’s mantle.

What is “Cratonic Thinning”?

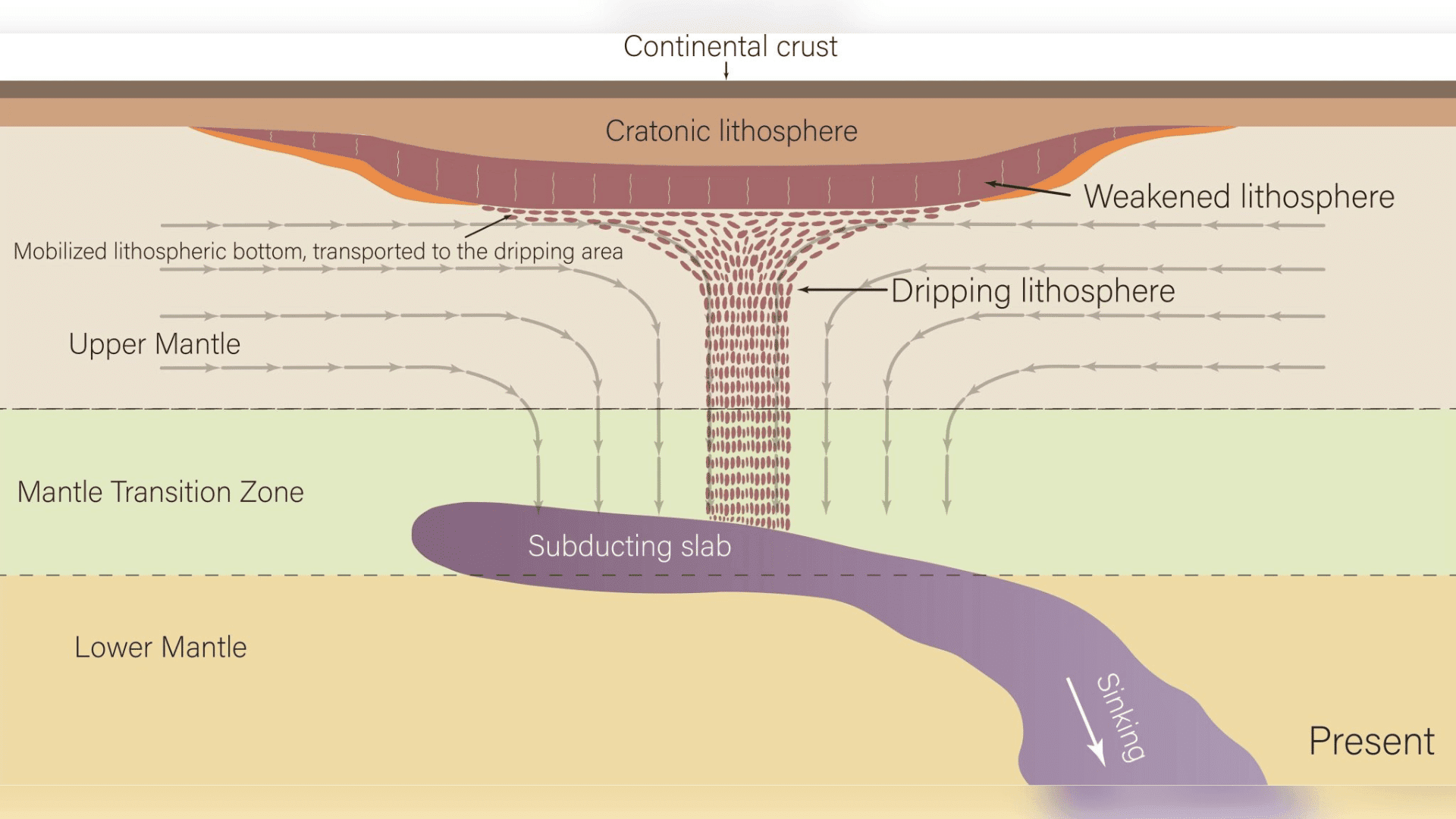

Cratons are ancient rock formations comprised of portions of the planet’s continents. These formations typically maintain stability for billions of years. Occasionally, geologic regions shift and cause layers of rock to disappear in a process known as cratonic thinning or cratonic dripping.

Though scientists haven’t had the chance to study this phenomenon actively, as the only documented examples occurred millions of years ago, that may soon change.

As they were developing a full-waveform seismic tomographic model of North America, UT Austin geoscientist Junlin Hua and colleagues noticed unusual activity at the border between Earth’s deep mantle and its thinner lithosphere.

“We made the observation that there could be something beneath the craton,” Hua, a study co-author now a professor at China’s University of Science and Technology, said in a statement. “Luckily, we also got the new idea about what drives this thinning.”

The model indicates the source is an oceanic tectonic plate known as the Farallon Plate, which is located beneath a large section of the Pacific Ocean. Though it’s separated from the craton by approximately 370 miles, researchers noticed the Farallon Plate seems to be redirecting mantle material flow into a path that melts away the bottom of the craton.

The activity resulting from this material flow is releasing volatile compounds, which are weakening the larger craton base. Hua and colleagues used a computer model to test the theory, running it with and without the inclusion of the Farallon Plate. The craton dripped when the tectonic plate was present and ceased when it was absent.

“You look at a model and say, ‘Is it real, are we overinterpreting the data or is it telling us something new about the Earth?’” said study co-author and planetary sciences professor Thorsten Becker. “But it does look like in many places that these blobs come and go, that it’s [showing us] a real thing.”

Though dripping appears to mainly center under the US Midwest, similar events typically cease when the tectonic plate’s remnants sink deeper into the mantle. Examining the phenomenon, however, could help researchers better understand Earth’s history.

“It helps us understand how do you make continents, how do you break them, and how do you recycle them [into the Earth,]” he said.