When an asteroid impacted the Earth sixty-six million years ago, the impact formed a 120-mile crater deep beneath what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. This resulted in debris flying through the air and raining down on Earth, causing wildfires and blocking out the sun which, eventually, led to the extinction of dinosaurs and other species. Though these were the main consequences, the impact of this asteroid left other marks on the Earth’s structure.

One such effect was an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of over 11, which sent huge Rayleigh waves rippling through the ground. Estimates suggest that these waves could have reached over 328 feet high.

“The effects of the earthquake, particularly the Rayleigh waves, resulted in disruption around the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) which is adjacent to the impact site,” the authors of a new study explain. “Carbonate shelves collapsed and unconsolidated clastic sediments on the shelves were mixed with water to form muds and suspensions which gravity mobilized to flow down the shelves and even into the depths of the GoM.”

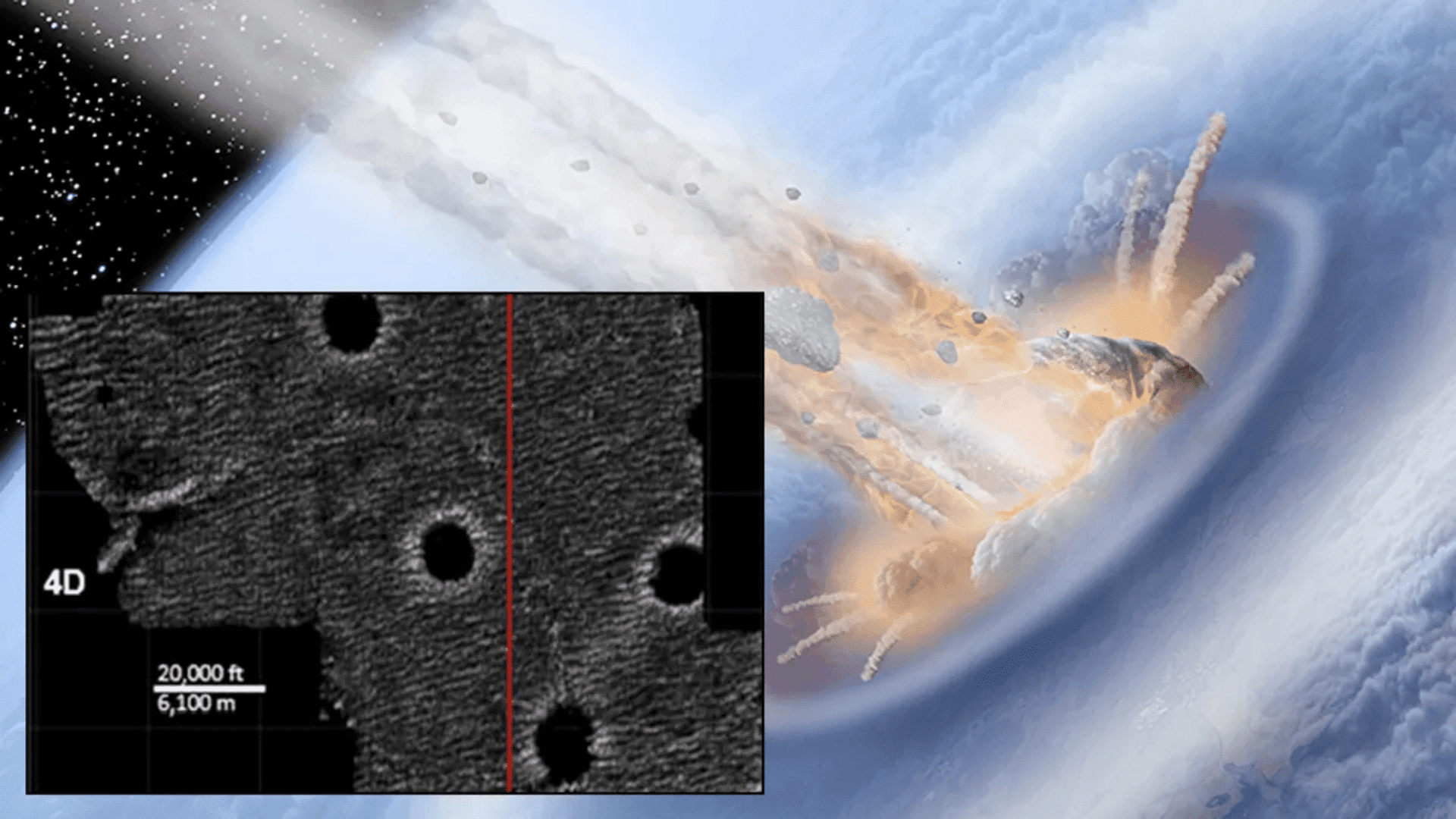

In 2021, a team led by Dr. Gary Kinsland of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette found evidence that the impact and subsequent tsunami left “megaripples” of sediment 53 feet high and 1,969 feet apart. In a new study led by Kinsland, the team further mapped the shelf using seismic data and found that these megaripples extend much further than expected.

“Megaripples exist everywhere in the data investigated upon/within the, once, fluidized marl muds of a mass transport deposit which was mobilized by Rayleigh waves from the Chicxulub Impact, about an hour before the tsunami reached the northern Gulf of Mexico (Louisiana),” the team explain in their new study.

Now that the authors of the study have expanded the search, they’ve found evidence of megaripples in a 900-square-mile area throughout the Gulf of Mexico and their varying formations along the upper shelf and the deep sea.

Though evidence of these megaripples has been discovered, how they formed remains a mystery. Despite this type of effect being more common in calmer environments, the team behind the new study suggests that the impact essentially “fluidized” a layer of sediment.

“I suspect that the fluidized sediment was moved into the ripple shapes by the tsunami and then retained the shapes much as whipped cream maintains shapes after the stirring ceases,” Kinsland stated to IFLScience, “I know of no ripples of the magnitude that we have found anywhere in the world.”