In footage more than ten years in the making, remote cameras in Norway have provided the first detailed look at polar bear cubs emerging from their dens.

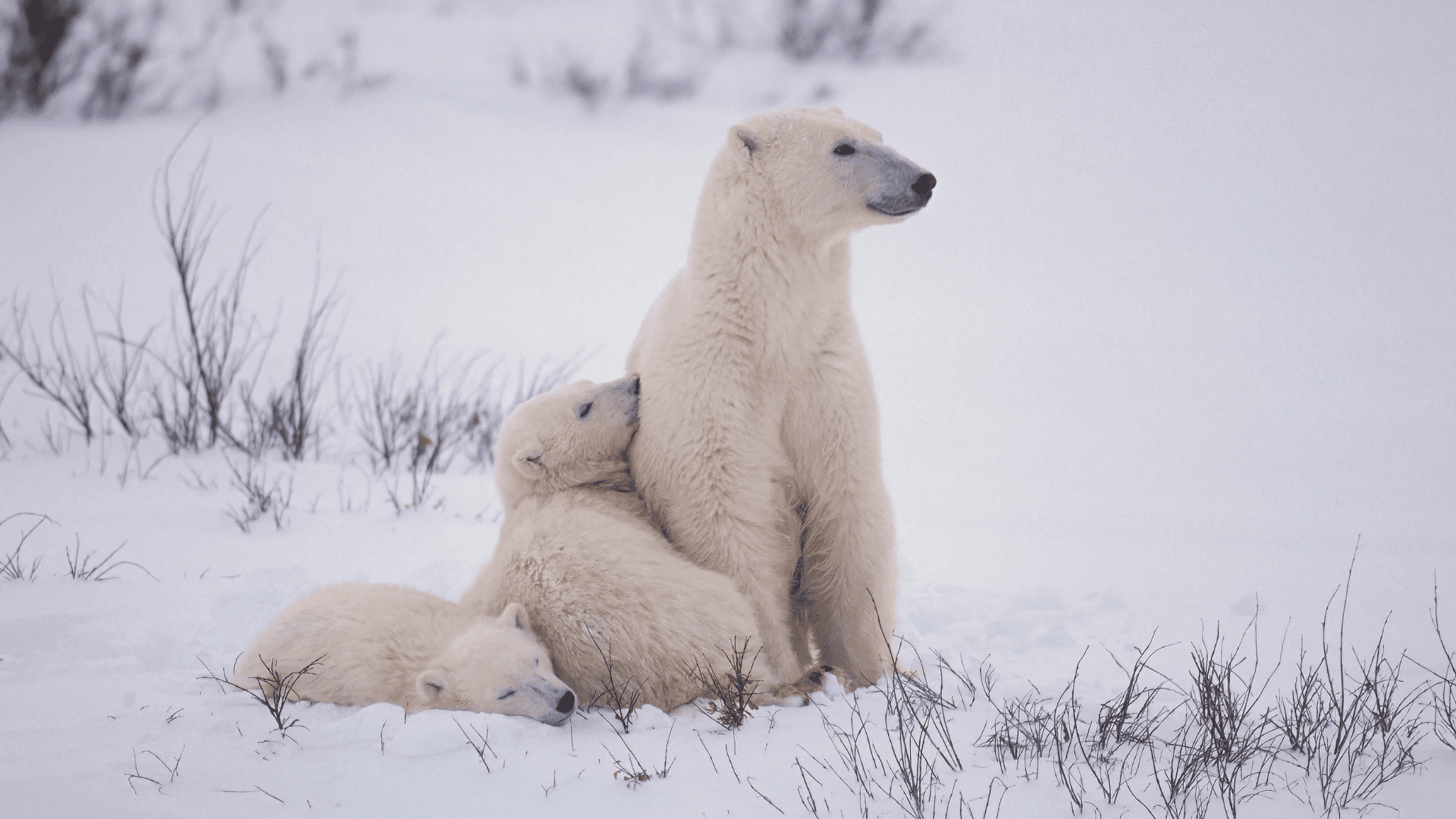

A polar bear cub spends the first few months of its life in a den of ice, their initially hairless body being protected from the cold by their mother and siblings. Cubs grow quickly on a diet of their mother’s milk and seal blubber, reaching approximately 10 kilograms by the time they leave the den in the spring of their first year. Shelter is crucial for cub survival in the first few years, particularly during the harsh winter months.

Cubs will dig dens under the snow up to a few meters deep with two openings: one scraped in the ceiling for ventilation, the other a doorway that the cubs will cross only once the weather warms. Though scientists have hoped to map out the best protections for bear dens, this style of shelter is notoriously difficult for scientists to observe.

An international team of researchers fitted female polar bears with GPS satellite collars, enabling them to track mother bears to their dens in Svalbard’s remote mountains. However, despite the time-lapse cameras set up at 13 dens over six years (2016–2020 and 2023), footage of mothers with cubs is still scarce.

“As the data from satellite radio collars were available for all the mothers, the observational data made it possible to tell how changes in activity and temperature recorded correspond with behavior,” says polar bear ecologist Jon Aars from the Norwegian Polar Institute.

The Svalbard polar bear families emerged from their dens around March 9th and abandoned them earlier than has been previously recorded for this population. Researchers hope to monitor the population further to determine whether this is a trend.

Collar and camera data showed that, after emerging from their dens, polar bears continued to live in and around them for an average of 12 days before setting off for the spring sea ice. Researchers also noted that cubs were only seen without their mothers 5 percent of the time, and some of the mothers were recorded moving their families to a different den.

“Every den we monitored had its own story; every data point adds to our understanding of this crucial time and supports more effective conservation strategies,” says lead author Louise Archer, an ecologist from the University of Toronto Scarborough.