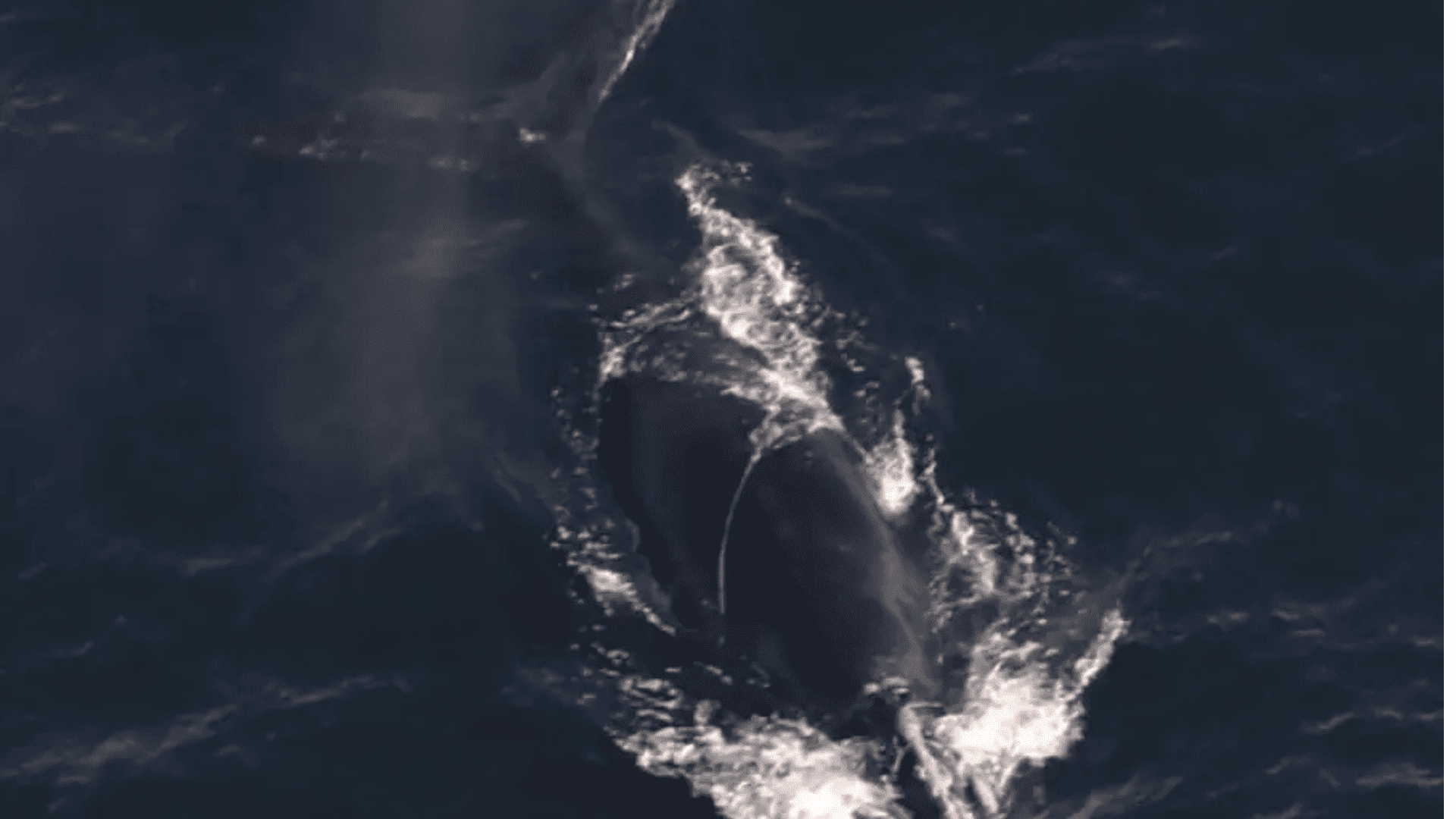

Right whales are some of the most endangered whales in the world. Only about 370 North Atlantic right whales remain. Scientists take to the air and sea to conduct whale surveys to spot some North Atlantic right whales and newborn calves. These surveys are critical to identifying and cataloging every newborn right whale. However, the surveys in the sky and on the water are imperfect.

Scientists are ramping up the effort to track the whales differently, especially in the Southeast, where the whales might migrate to give birth this time of year.

Listening for Whales

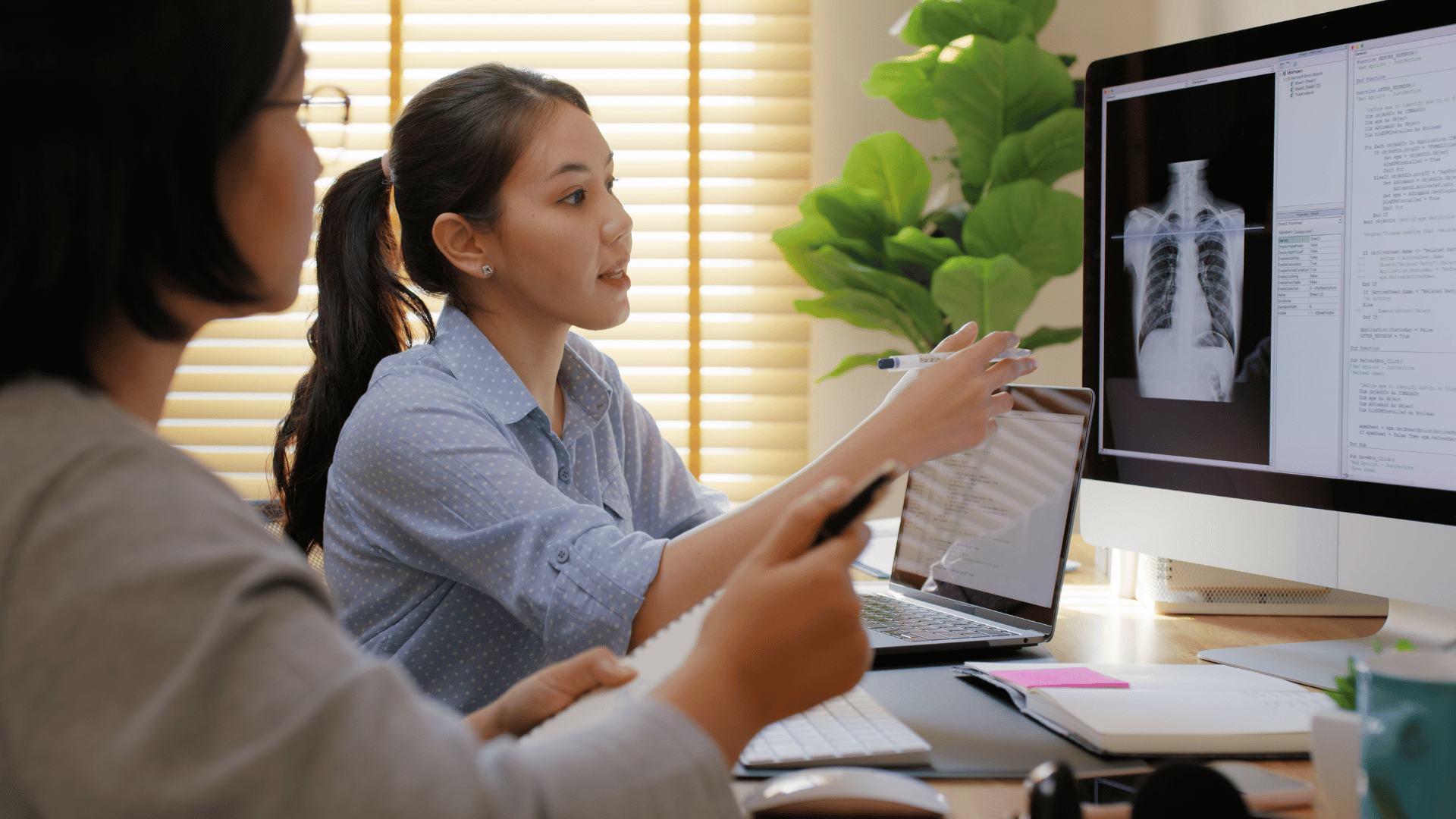

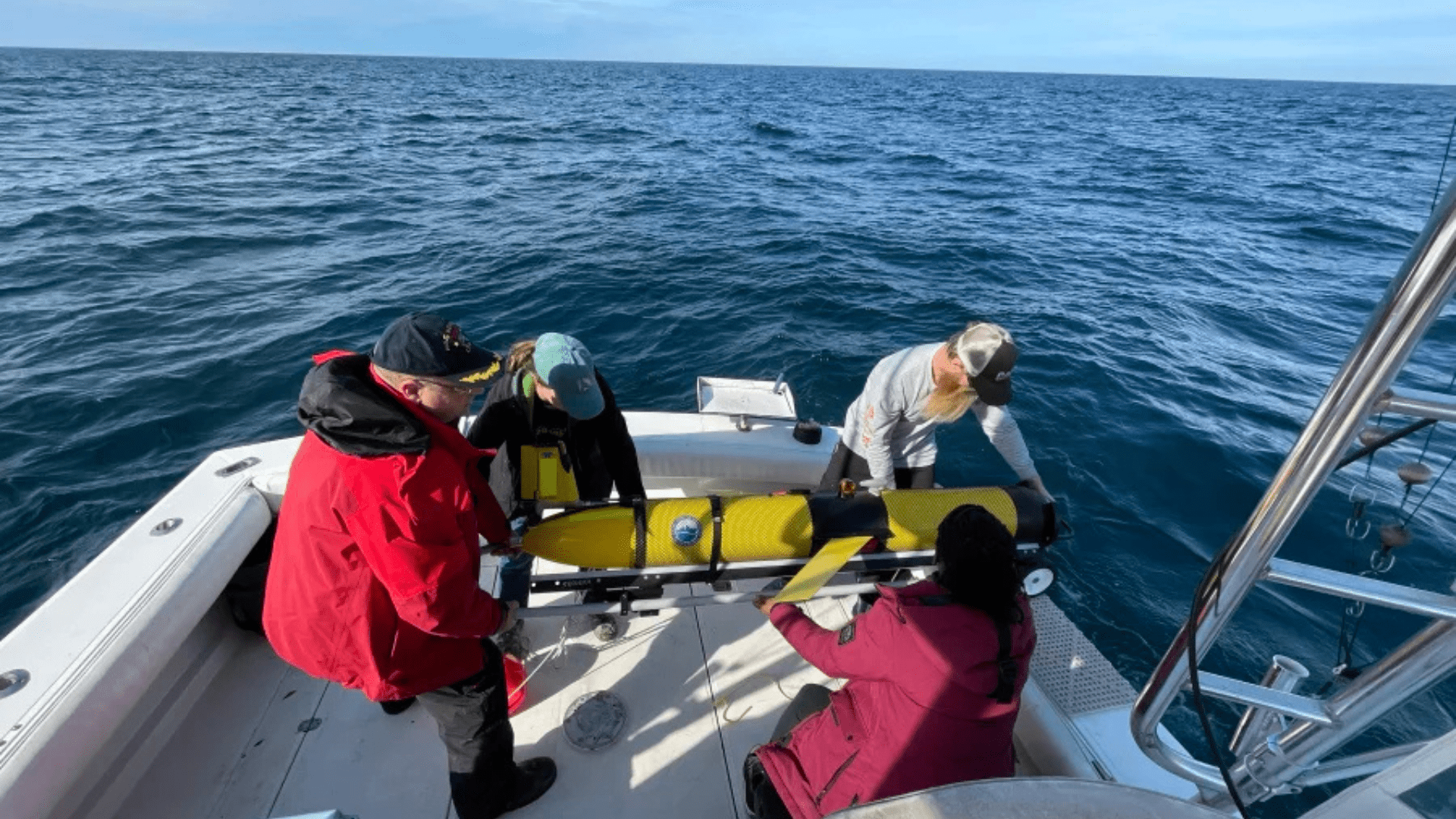

Catherine Edwards, a researcher at the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, and her team use tools to listen for underwater whales. Because of the winter weather, flying is limited. “Unfortunately, the weather in December, January, and February doesn’t always let flights happen,” she said.

Edwards and her team use passive acoustic detection, which involves supersensitive microphones floating in the water, to listen for whale sounds. Edwards said, “The biggest success we had from last year is we have the very first confirmed passive acoustic detection of right whales south of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.”

Similar technology is used extensively in the north, but the shallower waters in the southeastern U.S. make it difficult.

Protecting Right Whales

The Northern Atlantic right whale has been listed as endangered since 1970. There used to be thousands of the species. However, in the 19th century, the whaling industry labeled them the “right whales to hunt” because they were slow and swam near the surface. By the 1930s, when right whale hunting was banned, there were only about 100 left. In 2010, they bounced back to about 500 but dropped down to around 370 since.

“We’re at the point where the loss of a couple of animals could be the difference between recovery and extinction,” said University of South Carolina professor Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, working with Edwards to improve acoustic tracking in the South.

Humans are the main killers of right whales, according to a report from NPR. A common cause of death or injury comes from the whales getting trapped in fishing nets. In addition, the whales are commonly hit and killed by boats. Alerts go out to the boaters when a whale is spotted, but the current spotting effort still misses whales.

Large boats are limited to a 10-knot, or 11 mph, speed in whale-sensitive areas. However, studies from the advocacy group Oceana show that many ships go too fast. Unfortunately, enforcement doesn’t happen in real time. Shipping industry groups say that the speed limit doesn’t work for smaller boats because it’s dangerous for them to go that slow.

Meyer-Gutbrod hopes better tracking can convince the smaller vessels to slow down when they spot a whale voluntarily.

“As much as we want to see a strengthening of these regulations, we also need to increase effort into motivating higher compliance rates,” she said.