A team of international scientists plans to drill into an Icelandic volcano’s magma in search of limitless energy. Iceland’s Krafla volcano is no stranger to eruption; it has erupted over 30 times in the last 1,000 years, most recently in the 1980s. The Krafla Magma Testbed (KMT) intends to advance the understanding of how magma, or molten rock, behaves underground.

Drilling Volcanoes

Knowing how magma behaves underground helps forecast the risk of eruptions and pushes geothermal energy to new frontiers. In addition, it taps into the extremely hot and potentially unlimited energy of volcano power. Starting in 2027, the team will begin drilling the first two boreholes to create an “underground magma observatory,” about 1.2 miles under the ground.

“It’s like our moonshot,” professor of magmatic petrology and volcanology Yan Lavallée told BBC News. “It’s going to transform a lot of things.”

Scientists usually measure volcanic activity with tools like seismometers. However, we don’t know as much about magma underground as lava on the surface, Professor Lavallée explains. He added, “We’d like to instrument the magma so we can really listen to the pulse of the earth.” He says pressure and temperature sensors are the key parameters they need to probe, and they will be placed into the molten rock.

Volcano Energy

KMT’s second borehole will develop a testing platform for a new generation of geothermal power stations, which harness the full use of magma’s extreme temperatures. “Magma are extremely energetic. They are the heat source that powers the hydrothermal systems that lead to geothermal energy. Why not go to the source?” asks Prof Lavallée.

About 25% of Iceland’s electricity and around 85% of household heating is from geothermal sources. Geothermal power taps into hot fluids underground, which makes steam to drive turbines and generate electricity.

The Krafla power plant sits in a valley below and supplies electricity and hot water to around 30,000 homes. The team plans to drill just short of the magma itself. “The geothermal resource is located just above the magma body, and we believe that is around 500-600C,” said Bjarni Pálsson, the executive director of geothermal development at national power provider Landsvirkjun.

Lives and Money

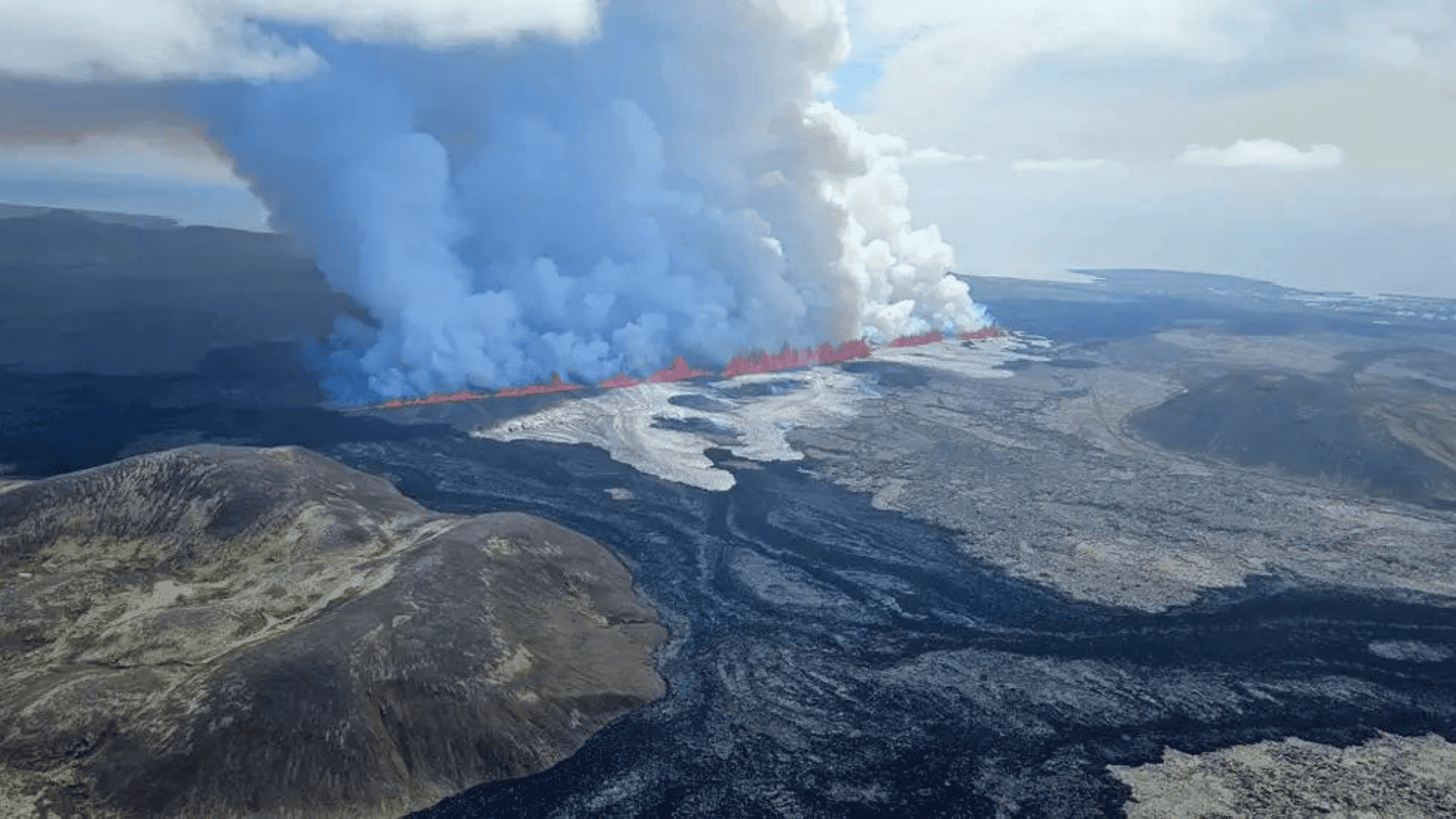

Approximately 800 million people globally live within 100km (62.1 miles) of hazardous active volcanoes. Iceland alone has 33 active volcano systems and sits on the rift where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates pull apart. Earlier this year, a wave of eight eruptions in the Reykanes peninsula damaged infrastructure and upended communities. The latest of the eruptions occurred at the end of May.

Bjorn Guðmundsson, who is leading the team of scientists, also pointed to Eyjafjallajökull. In 2010, it caused havoc when an ash cloud caused over 100,000 flight cancellations, which cost £3bn ($3.95bn). He said, “If we’d been better able to predict that eruption, it could have saved a lot of money.”

Drilling into volcanoes sounds risky, but Guðmundsson disagrees. “We don’t believe that sticking a needle into a huge magma chamber will create an explosive effect,” he said. “This happened in 2009, and they found out that they’d probably done this before without even knowing it. We believe it’s safe.”

The team’s work will take years, but they believe that it will all be worth it in the end. At the finish line is the potential for advanced forecasting and supercharged volcano power.