According to new research, Stonehenge’s Altar Stone, which resides at the center of the ancient monument in southern England, was likely moved approximately 5,000 years ago over 435 miles from what’s now northeastern Scotland.

The Altar Stone is the largest of the bluestones used in the monument and weighs approximately 13,277 pounds. A new study has disproven an old theory that the stone originated in current-day Wales.

“This stone has traveled an awful long way — at least 700 km — and this is the longest recorded journey for any stone used in a monument at that period,” said study coauthor Nick Pearce, a professor in the Department of Geography and Earth sciences at Aberystwyth University in Wales, in a statement. “The distance traveled is astonishing for the time.”

The construction of Stonehenge occurred in several phases, with the Altar Stone being built during the second construction phase between 2620 and 2480 BC. The discovery suggests that ancient British citizens were advanced and capable of moving massive stones, potentially through maritime means.

“Our discovery of the Altar Stone’s origins highlights a significant level of societal coordination during the Neolithic period and helps paint a fascinating picture of prehistoric Britain,” said study coauthor Chris Kirkland, a professor and leader of the Timescales of Mineral Systems Group at Curtin University’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Australia, in a statement. “Transporting such massive cargo overland from Scotland to southern England would have been extremely challenging, indicating a likely marine shipping route along the coast of Britain. This implies long-distance trade networks and a higher level of societal organisation than is widely understood to have existed during the Neolithic period in Britain.”

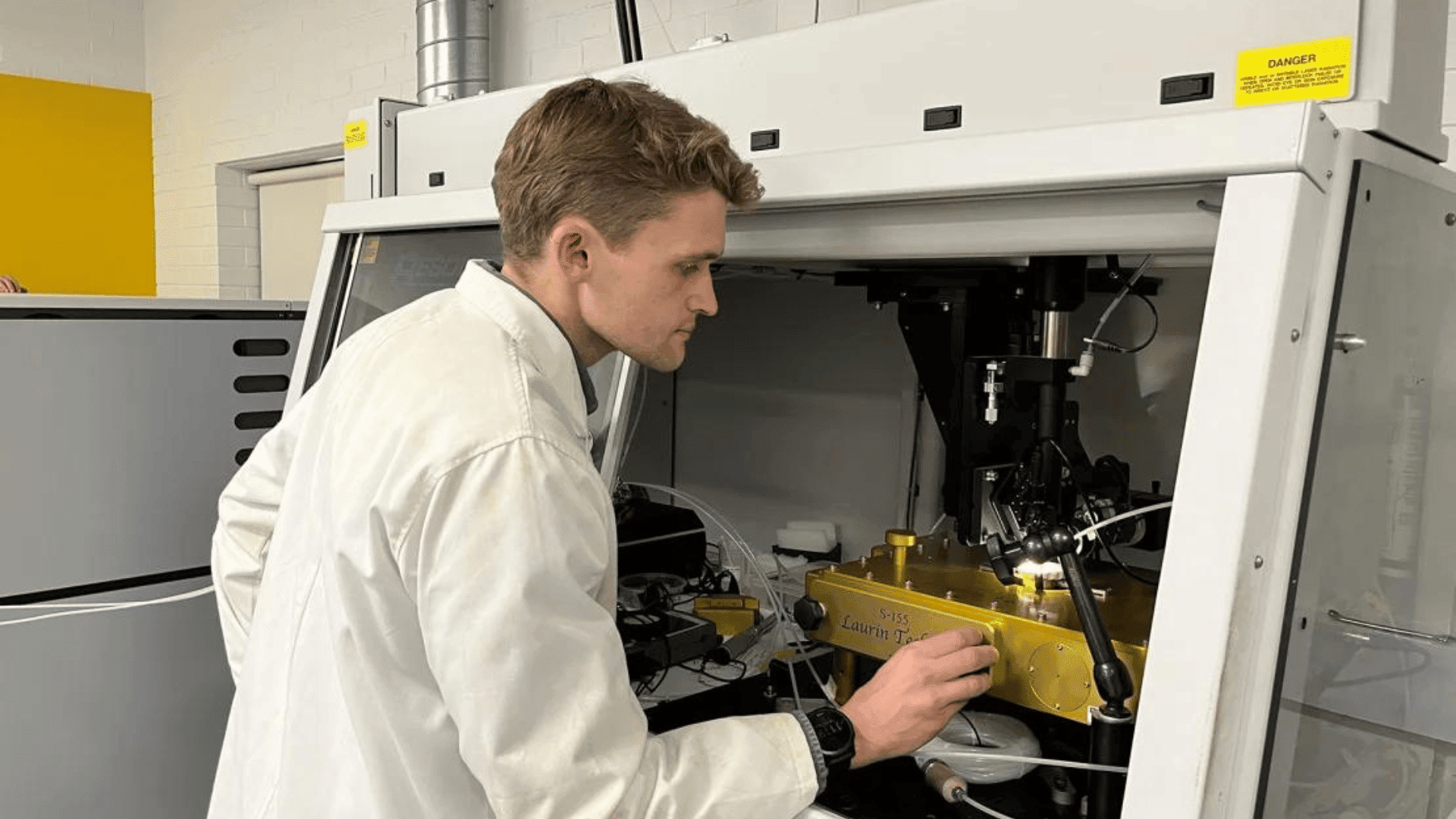

Researchers in the study analyzed the age and chemistry of the stone’s mineral grains to gauge its age. Their analysis revealed the presence of zircon, apatite, and rutile grains dating to different times. The zircon dated to between 1 billion and 2 billion years ago, while the apatite and rutile grains dated to between 458 million and 470 million years ago.

Using the mineral grains, the team built a “chemical footprint” that could be used to track similar sediments and rocks across Europe. The grains best matched a group of sedimentary rocks known as Old Red Sandstone located in the Orcadian Basin in northeast Scotland, which differs drastically from stones found in Wales.

“It’s thrilling to know that our chemical analysis and dating work has finally unlocked this great mystery,” said study coauthor Richard Bevins, honorary professor in the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University, in a statement. “The hunt will still very much be on to pin down where exactly in the northeast of Scotland the Altar Stone came from.”