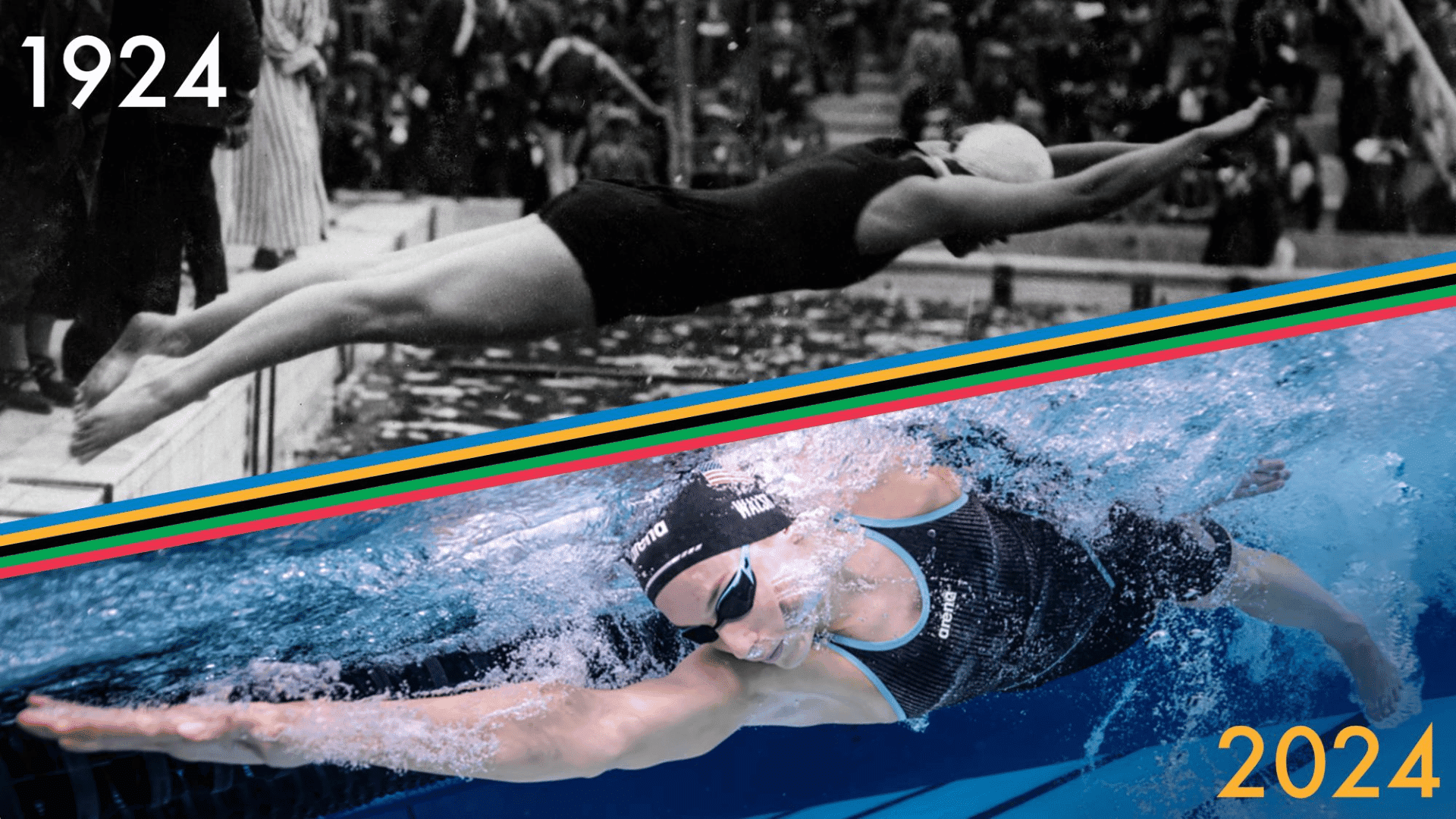

The swimwear used in the Paris 2024 Olympics has evolved significantly from the heavy woolen briefs that the games began with.

Designing swimwear appropriate for fast swimming involves an awareness of the sport’s physics. Water is over 700 times denser and 55 times more viscous than air, meaning that it has a much higher resistance to flow and is more difficult to move through.

“Basically, there are two forces. Thrust is what propels you forward and drag which resists you,” Northwestern University engineer and fluid dynamicist Timothy Wei tells Popular Science. “That’s the battle the swimmer has to carry, and the faster the swimmer goes, the more the drag will be.”

There are three different types of drag that swimmers face: pressure drag, viscous or friction drag, and wave drag. Pressure drag is similar to sticking an arm out of a car window and feeling the force pushing it backwards, and viscous or friction drag is a rubbing motion when the water hits the surface of a swimmer’s body.

“Wave drag is like when you look at a boat and there’s a wave in front of it. It’s basically water piling up in front of the boat and you have to push that out of the way,” says Wei. “That only happens because there’s a free surface. There’s air on top of the water.”

Though a swimmer’s technique is important when working against these forms of drag, the swimsuit design can also help.

Early iterations of Olympic “swimming costumes” were like wool romper sweaters. According to the Fashion Institute of Technology, knitted swimsuits tended to become misshapen when wet, absorbing a lot of water. They also sagged, and the lost material would slow swimmers down.

The first silk swimsuits appeared in 1912. The sleeker designs didn’t absorb as much water, which allowed the athletes to perform better. By the mid-20th century through the turn of the 21st century, nylon and then lycra continued to progress the smoother and tighter swimwear technology.

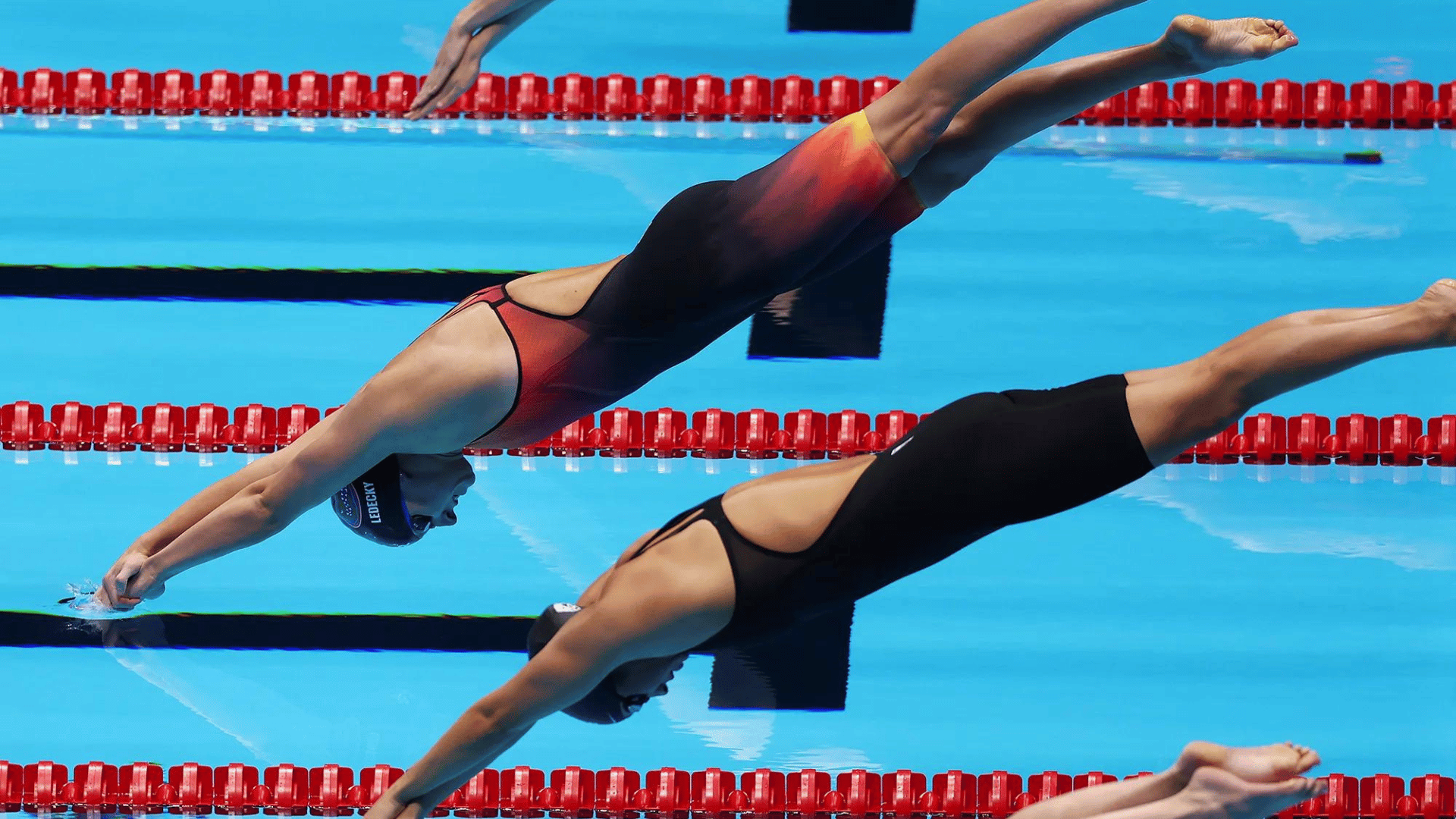

The swimsuits for the Paris 2024 Olympics were designed to simultaneously overcome the three types of drag while also adhering to the standards set by World Aquatics’ regulations. The pieces also need the right balance between compression and flexibility to ensure the swimmer’s muscles don’t tire out.

Swimmers sponsored by Speedo sported the LZR Intent 2.0 and LZR Valor 2.0, which contained a coating technology that was originally used to protect satellites. TYR athletes will compete in the TYR Venzo, which was developed by analyzing drag from a microscopic perspective.

Arena-sponsored swimmers from multiple countries will wear the PowerSkin Primo, made with tensoelastic fabric that uses the tension within the fabric to create high compression while stretching it as little as possible.

The yarns are made with thermoplastic (TPU), and the suit is chlorine-resistant. It provides this high amount of compression with half the stretch and is hydrophobic, so water will slide off and move away from the swimmer.

“The suit going to Paris is amazing in that it can provide high compression, but it has a lot of elasticity,” said the head of product development for Arena Greg Steyger, telling Popular Science. “It not only allows the muscles to perform at the peak without restricting them and manages to fit more bodies because of the amount of stretch.”