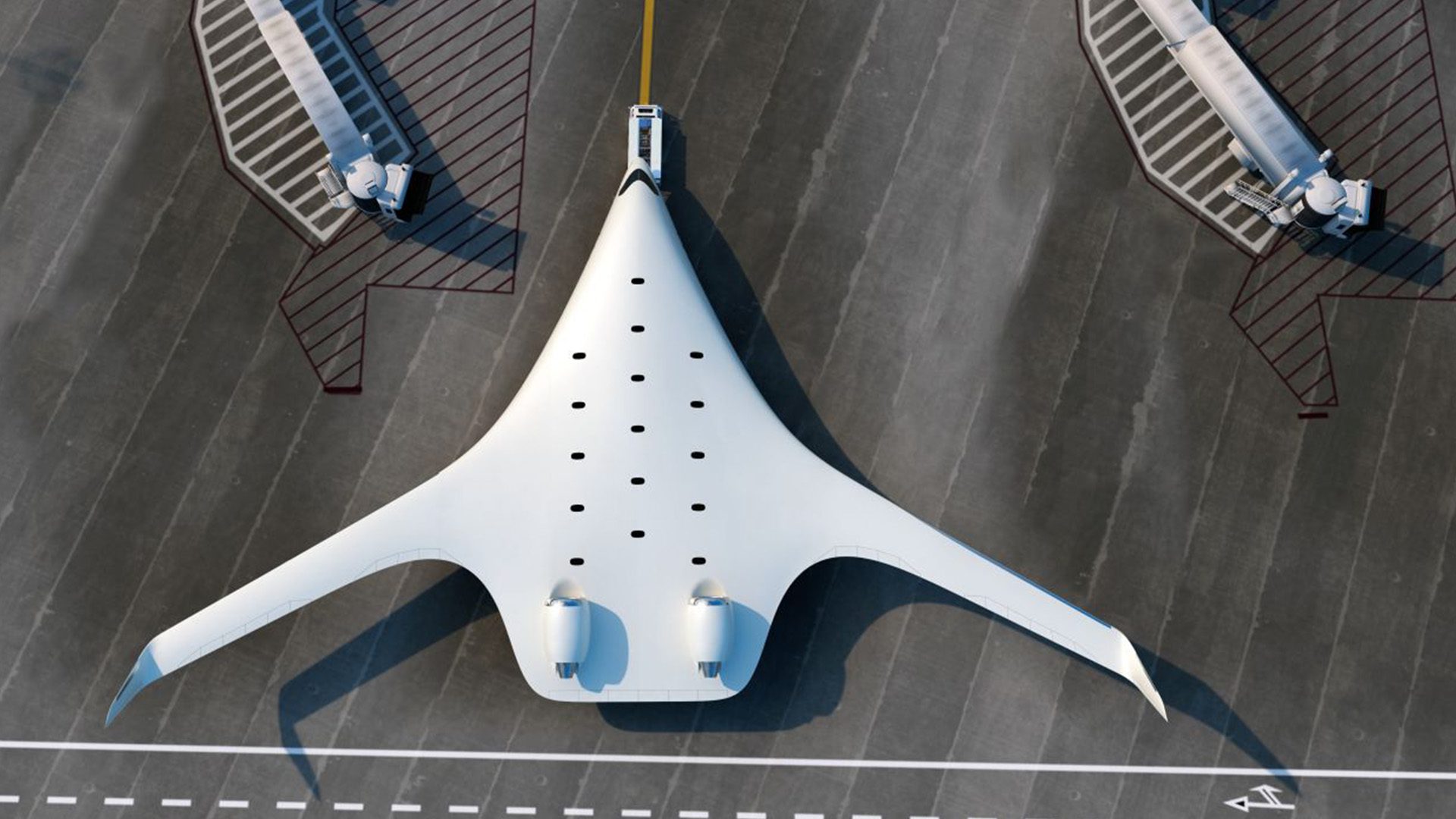

As the commercial aviation industry attempts to find new means of reducing carbon emissions, companies like JetZero are beginning to move away from traditional plane designs in favor of the “blended wing body” design.

The “flying wing” design is used by military aircraft such as the B-2 bomber, but the blended wing design has more volume in the middle section. A few companies are tinkering with the design, including Boeing and Airbus, but the California-based JetZero has set an ambitious goal of putting a blended-wing aircraft into service as early as 2030.

“We feel very strongly about a path to zero emissions in big jets, and the blended wing airframe can deliver 50% lower fuel burn and emissions,” says Tom O’Leary, co-founder and CEO of JetZero. “That is a staggering leap forward in comparison to what the industry is used to.”

A hybrid between a flying wing and the traditional “tube and wing”, the blended wing design allows the entire aircraft to generate life and minimize drag. According to NASA, this shape “helps to increase fuel economy and creates larger payload (cargo or passenger) areas in the center body portion of the aircraft.”

The agency has tested the design through one of its experimental planes, the X-48. Between 2007 and 2012, over 120 test flights of two unmanned, remote-controlled X-48s demonstrated the viability of the design.

“An aircraft of this type would have a wingspan slightly greater than a Boeing 747 and could operate from existing airport terminals,” the agency says, adding that the plane would also “weigh less, generate less noise and emissions, and cost less to operate than an equally advanced conventional transport aircraft.”

The one technical challenge that has held back manufacturers is the pressurization of a non-cylindrical fuselage is more difficult and the tube-shaped plane is better able to handle the expansion and contraction cycles in flight.

“If you think about a ‘tube and wing,’ it separates the loads — you have the pressurization load on the tube, and the bending loads on the wings. But a blended wing essentially blends those together. Only now can we do that with composite materials that are both light and strong.”

JetZero wants to simultaneously develop three variants: a cargo plane, a fuel tanker, and a passenger plane. The US Air Force recently awarded $235 million to develop a full-scale demonstrator of the fuel tanker design. As the first flight of this variant is expected by 2027, this design could perhaps support and influence the development of commercial models.

Although JetZero plans to initially utilize engines from today’s narrowbody aircraft like the Boeing 737, the plan is to eventually move to a completely emission-free propulsion powered by hydrogen.

While NASA and Airbus have estimated a 20% reduction in fuel use from their designs, JetZero has estimated a 50% reduction in fuel use. The US Air Force has also stated that a blended-wing aircraft could “improve aerodynamic efficiency by at least 30% over current Air Force tanker and mobility aircraft.”

The new shape of the aircraft would also drastically alter the look and feel of the plane interior compared to a widebody aircraft. Whereas a typical single-aisle plane has three by three seats, the blended wing body plane could have up to 15 or 20 rows across the cabin.

“The blended wing body aircraft holds immense promise as a game changer in the aviation industry, offering the potential for improved fuel efficiency, enhanced payload capacity, and innovative control systems. However, addressing the aerodynamic complexities, ensuring structural integrity, navigating regulatory hurdles, and adapting airport infrastructure are formidable challenges that must be overcome for it to become a reality,” says Bailey Miles, an aviation analyst at consulting firm AviationValues.