Environmental migration is a historical problem with a daunting future—the most widely repeated prediction is that there could be up to 200 million environmental migrants by 2050. This number is ten times bigger than today’s entire documented refugee and internally displaced populations. If this came to pass, it would mean by 2050 out of every 45 people in the world, 12 would have been displaced by climate change. However, this number is not final; there are ways to mitigate some of the forthcoming issues associated with environmental migration.

Environmental Migration Definition

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), environmental migration consists of migrants who are obliged to leave their homes or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within their country or abroad, due to sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions. This definition is intentionally broad so that it accounts for the wide range of movements due to the array of environmental issues worldwide.

For example, environmental migration encompasses climate migration, which is where the specific type of environmental change influencing a move is solely due to climate change. Environmental migration also includes planned relocation, a planned process where people move away from their homes, are settled in a new location and are provided with conditions for rebuilding their lives due to disasters or environmental degradation. Planned relocation is typically used to classify relocations within national borders under the authority of the State.

Environmental migrants are also not legally considered refugees according to international refugee law. A refugee is a legal term describing people who leave their home because of persecution of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion. Since the environment is not classified here, these people are not refugees.

Historical Examples of Environmental Migration

Environmental migration has existed practically since the beginning of society itself, even becoming a driving force of the formation of the first large urban societies. For example, the societies of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia emerged as people migrated away from the dry rangelands into more fertile river valleys. This resulted in densely packed populations needing to manage scarce resources, influencing the need to form a complex society.

Environmental migration has continued to play a role in forming societies, countries, and cultures. For example, the drought in the Middle East in the 8th century played a huge role in the Muslim expansion into the Mediterranean and southern Europe. It also influenced a massive migration to California in the 1930s during the Dust Bowl. The Dust Bowl was the result of multiple years of below-average rainfall and above-average temperatures in the Great Plains of the United States, coinciding with the Great Depression. This caused a widespread failure of small farms, influencing about 300,000 people to leave the region, many going to California.

Photo Credit: Medium

More recently, one of the biggest examples of environmental migration occurred in 1998 in Bangladesh when the country faced some of the worst floodings in living memory. The floods left an estimated 21 million people homeless and devastated the country’s infrastructure and agriculture base. Then, in 2009, Cyclone Aila displaced approximately two million more Bangladeshis. Over 10 years later, tens of thousands of those left homeless are still not back to their homes and have moved into informal settlements or slums.

The IOM’s research on Bangladesh finds that it is a clear case study of environmental migration that demonstrates what can happen when a governing body does not intervene in major environmental events. Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to climate change due to its low-lying geography and coastline prone to cyclones and erosion from sea-level rise. However, its problems are not isolated. There are many more past examples of environmental migration, and present and future problems must be considered to prevent any of the damage, whether it is physical, economic, or mental.

Current & Future State of Environmental Migration

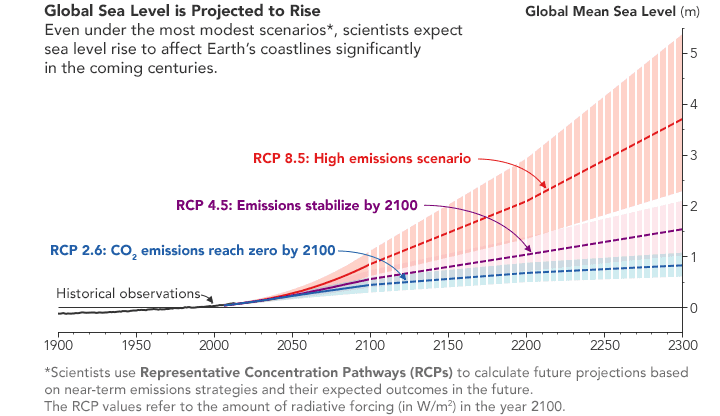

The biggest source of current and future environmental migration is rising sea levels. In its 2019 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected that the global sea level will rise 0.6 to 1.1 meters (2 to 3.5 feet) by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions remain at high rates. If countries cut their emissions significantly (RCP2.6), the IPCC expects 0.3 to 0.6 meters (1 to 2 feet) of sea-level rise by 2100.

The rising sea levels have already affected many nations. The clearest examples are in the Pacific Islands where the sea levels are already rising at a rate of 12 millimeters per year. Sea levels have already submerged eight islands with two more on the brink of disappearing, prompting a wave of migration to larger countries. By 2100, it is estimated that 48 islands overall will be lost to the rising ocean. However, the relatively small population (2.3 million people spread across 11 countries) and remote location of the Pacific Islands means that they garner little international and media attention.

In addition to rising sea levels, the average temperature of the Earth is expected to increase by the end of the century. IPCC researchers say we need to keep warming to under 2 degrees Celcius before the end of the 21st century to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. This is achievable if we start decreasing our greenhouse gas emissions downward now.

A major example of current and future damage due to rising average temperature is in Central America. The average temperature in Central America has increased by 0.5 degrees Celsius since 1950, and it is projected to rise another 1-2 degrees before 2050. This impacts weather patterns, rainfall, soil quality, crops’ susceptibility to disease, hurting farmers and local economies. Storms, floods, and droughts have been increasing in the region as well. It is projected that floods will increase in Honduras by 60%, and in arid regions in Guatemala, arid regions will increase and damage agricultural areas. El Salvador alone is projected to lose 10-28% of its coastline before the end of the century, combining rising temperatures and rising sea levels. All of these issues will increase environmental migration in this region because of a lack of economic future and an increase in danger.

What Can Be Done?

The major solutions to mitigating environmental migration are the same solutions used to decrease greenhouse gas emissions. For example, increasingly using renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower. These sources provide clean, zero-emission energy around the world, and they are expanding. However, they are variable with the weather or seasons and some are not available worldwide. This means that they still rely on fossil fuels for baseload power.

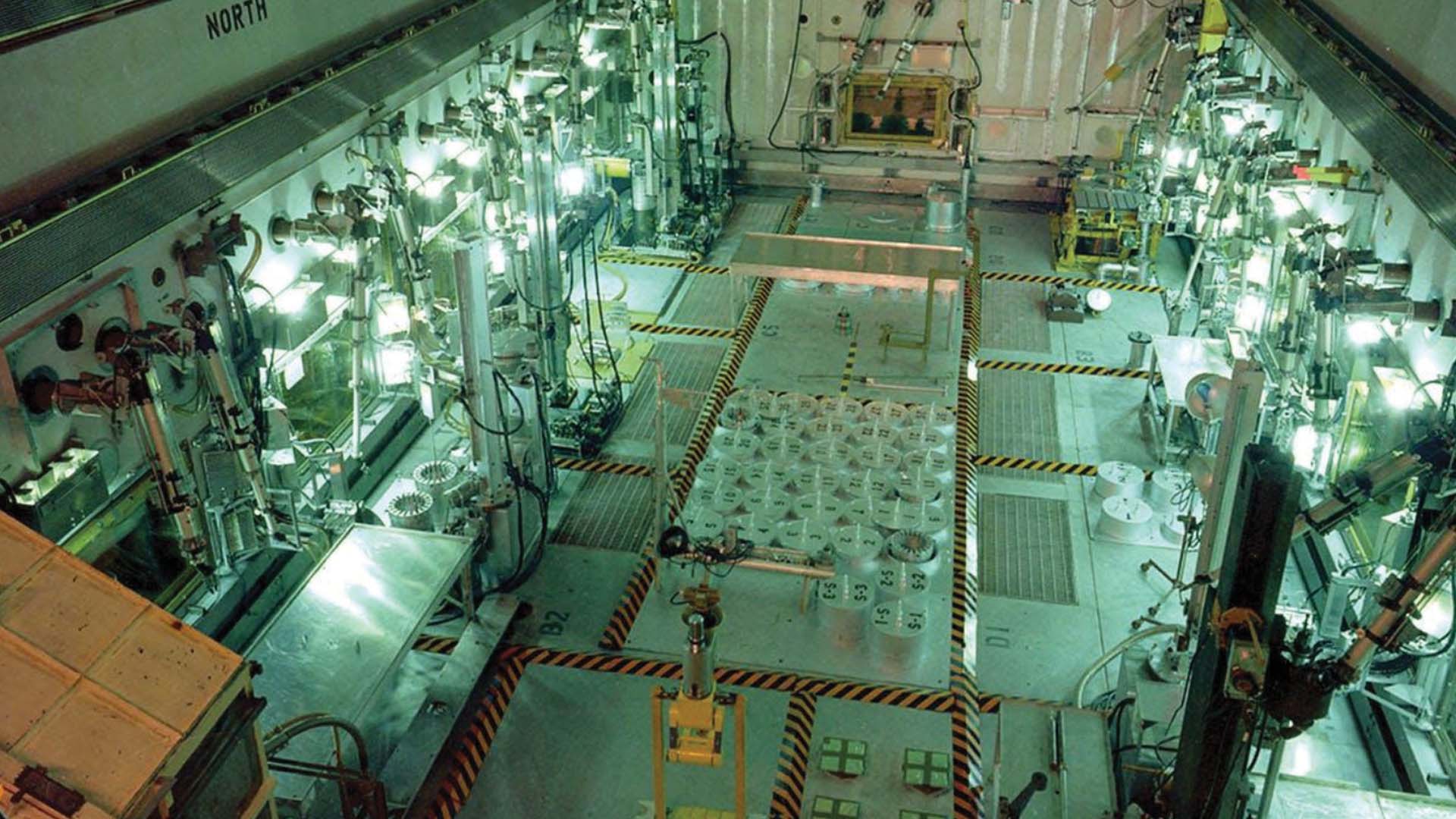

The U.S. Energy Information Administration found that the expansion of renewables in the US is mostly supported by steady baseload power from fossil fuel power plants with 60% of total electricity generation, followed by nuclear at 21%. Nuclear energy is the better alternative to fossil fuels to support renewable energy, and it is a growing power source. Additionally, nuclear energy gives off zero carbon emissions and can produce electricity 24/7, 365 days a year, regardless of if the wind blows or the sun shines. With renewable energy forecasted to grow (it increased 100% in its share of the U.S. energy mix between 2000 and 2018), nuclear energy is more important than ever to decrease greenhouse emissions to reduce environmental migration as well.

While renewable energy coupled with nuclear energy is a step forward in reducing greenhouse gas emissions thus the need for environmental migration, ample and wide-reaching solutions must be in place for when environmental migration is needed. A great deal of this responsibility falls on the state or country.

The main priority should be to find solutions that allow people to stay in their homes and give them the means to adapt to changing environmental conditions. This aims to avoid instances of desperate migration and its associated tragedies. However, where environmental impacts are too intense, another priority must be solutions and systems put in place for people to be able to migrate safely and through regular channels. As a last resort measure, planned relocations of populations must be conducted. This means organizing the relocation of entire villages and communities away from areas bearing the brunt of climate change impacts. With environmental migration forecasted to increase, these plans and solutions are critical.