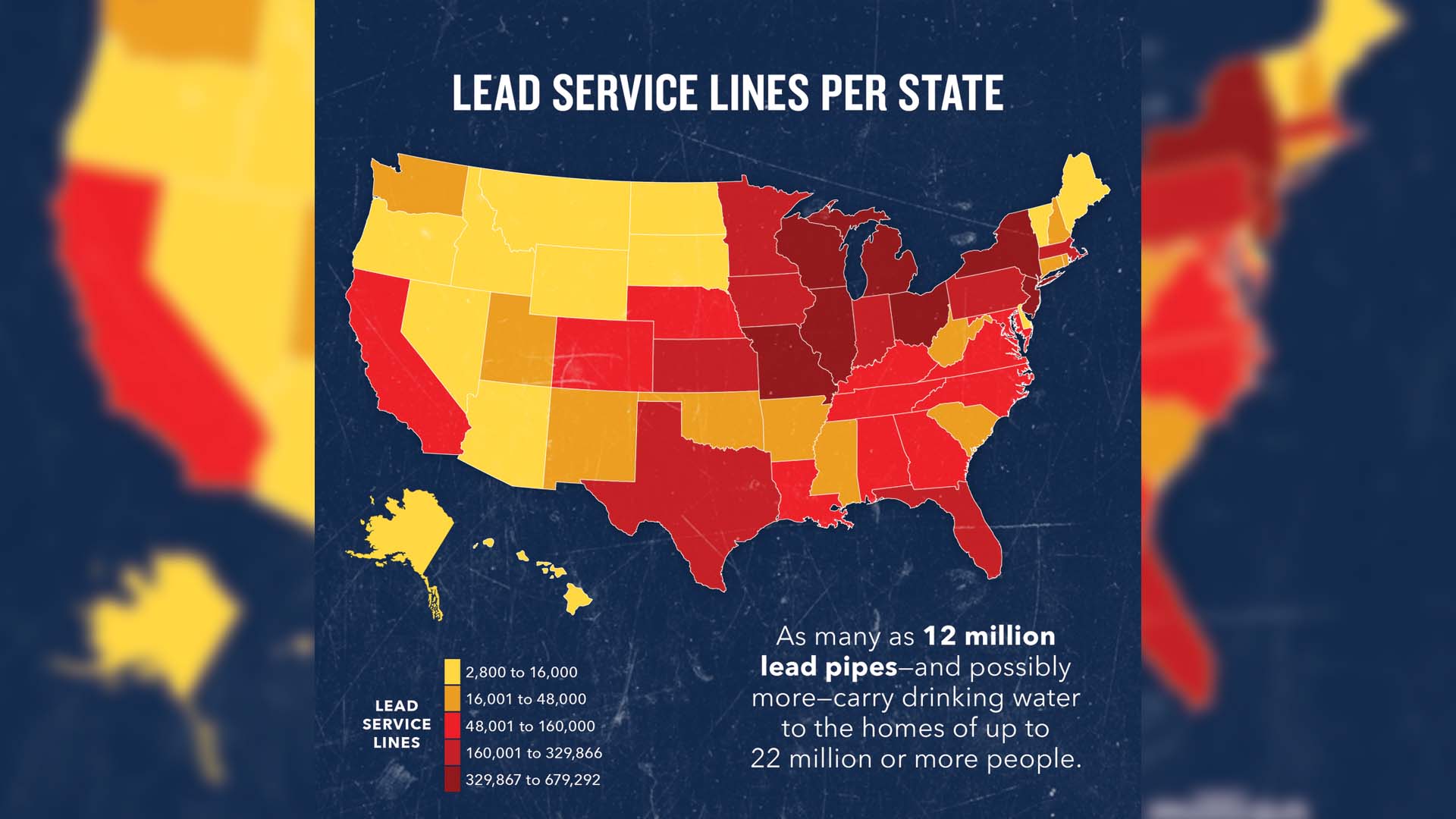

Did you know that an estimated 15 million to 22 million Americans still drink water that entered their home through a lead pipe? America’s lead water pipe problem is a continuing issue that must be addressed.

How many lead water pipes remain in America?

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimates that there is a range of 9.7 million to 12.8 million pipes that are, or may be, lead, spread across all 50 states. Most states don’t even have data on lead water pipes in their state, meaning that they don’t know how many lead pipes they have. Almost all of America’s remaining lead pipes are due to be replaced by the middle of the century, but replacing these water lines is costly and inconvenient. The American Water Works Association estimates that completely replacing all lead pipes would cost a trillion dollars.

Why were lead water pipes used in the first place?

Lead water pipes have been used since around 200 B.C. when Roman engineers replaced their water system with lead pipes due to their malleability and abundance. Fast forward to the 19th century, lead pipes were still used because they were dense and durable, but also soft and malleable. Also, lead doesn’t rust easily or decay from soil contact like other pipes. As a result, lead was perfect for smaller pipes that branch off from larger water mains and carry water to buildings, where they must twist and bend to get to sinks, showers, and toilets.

By 1900, 23 of the 25 largest U.S. cities, and 85 percent of all cities, used primarily lead service lines. Many local building codes also mandated that service lines must use lead pipes for construction.

Why are lead pipes still in the ground?

After a great deal of research and studies into the detrimental health effects of lead pipes, Congress banned the installation of lead pipes in 1986. However, they allowed the ones already in use to remain in the ground. Today, utilities often rely on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) tests and treatments to mitigate lead instead of replacing the pipes.

For the treatments, the EPA issued the Lead and Copper Rule in 1991 to set health standards for lead and copper in drinking water. Under this rule, city utilities are supposed to add chemical treatments to their water that coat the inside of lead pipes to create a barrier and seal off the lead from the water.

Even when they’re done correctly, however, the coatings can quickly break down if the chemical balance is disturbed, and some lead can still get into the water. In Flint, Michigan, all it took for the protective minerals to dissipate was switching Flint’s drinking water source from Lake Huron to the more polluted Flint River. In other cases, shaking caused by nearby construction was enough to temporarily shake loose protective coatings inside lead water pipes and cause lead levels to spike thousands of times higher than the EPA’s required levels.

As for the EPA’s tests, data from Chicago and Michigan reveal that many people may be consuming higher levels of lead than the EPA testing method can detect. Michigan and Chicago’s utilities are no different than any other, they just conducted more rigorous testing than the EPA requires. If other cities did the same, they would likely find similar levels of lead.

How much lead is too much in water?

According to the World Health Organization, there is no known level of lead exposure that is considered safe. Lead accumulates in our bodies over time, meaning that most lead poisoning problems occur when small amounts of lead are consumed over time, building up and causing health problems.

Because they absorb more lead than adults and because their nervous systems are still developing, children under 6 are the most susceptible to lead exposure. Even small amounts of lead in the blood in children can inhibit brain development and intellectual ability. Criminal behavior has also been linked to lead poisoning. Lead is harmful to adults as well, causing cardiovascular effects, decreased kidney function, and reproductive problems in both men and women.

How can you tell if there is lead in your water?

Short answer? You can’t. Lead dissolved in water cannot be seen, tasted, or smelled—testing your water is the only sure way of telling whether there are harmful quantities of lead in your drinking water. You can test your water at a nearby DEP-Certified lab, at a water filtration comany, or you can contact your water supplier and ask if they offer water testing.

Photo Credit: The Denver Post

What is the government doing about this?

Lead pipe replacement is one of the White House’s top infrastructure priorities, with a goal to replace 100% of the nation’s lead service lines as part of its American Jobs Plan. In March, Biden announced that he wants Congress to invest $45 billion to the EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and in Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act grants as routes to lead pipe replacement. The Senate version of the bill remains in committee, but lead pipe replacement is expected to be included in the final version.

What is a better pipe option?

Due to the multitude of health concerns, every other type of water pipe is a better option than lead. One type of pipe that has been used to replace lead pipes is a ductile iron pipe. These pipes are more durable and last much longer than steel, cast iron, and PVC pipes. They are made out of 90% recycled material and are 100% recyclable, making them much more sustainable too. Many towns have been switching to ductile iron pipes made by companies like U.S. Pipe, and they could be the best option for new pipes when a town replaces their lead ones.

To watch ductile iron pipe be made and installed, stream Tomorrow World Today’s “Pipe Dreams” HERE.